19 December 2020, NIICE Commentary 6606

Dr. Raymond Kwun-Sun Lau

Hong Kong, as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) under China since 1997, has been granted a high degree of autonomy under the territory’s mini-constitution, known as the Basic Law. Article 137 of the Basic Law, in particular, stipulates that ‘educational institutions of all kinds may retain their autonomy and enjoy academic freedom. They may continue to recruit staff and use teaching materials from outside the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’. In this sense, universities in Hong Kong have been guaranteed to enjoy one of the most academically free and autonomous atmospheres in Asia.

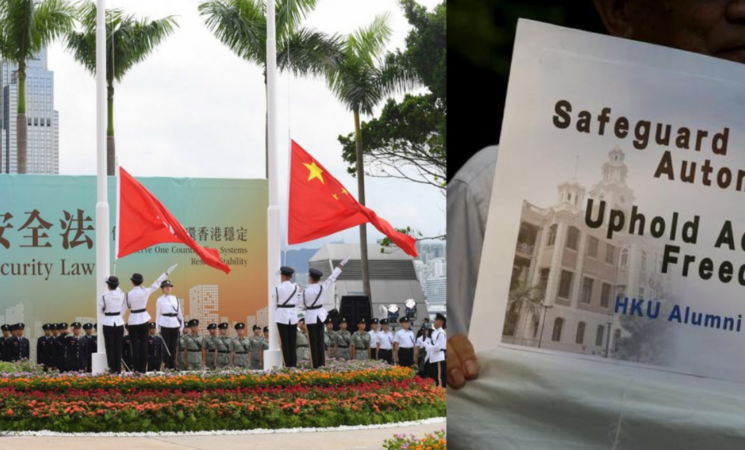

Yet, the future of academic freedom in Hong Kong’s universities is called into question since the Chinese government unilaterally imposed the wide-ranging national security law (NSL) on Hong Kong in July this year. Under the NSL, a wide range of speech and activity on campuses could be considered a serious crime in the list of offences, namely ‘secession’, ‘subversion’, ‘terrorist activities’ and ‘collusion with a foreign country’. Perhaps more worryingly, this new law not only applies within Hong Kong but also outside the SAR. The extraterritorial reach of the new law means, at least potentially, non-Hong Kong residents/ foreign nationals who speak out against government misconduct or advocate sanctions against Beijing could be prosecuted upon entering Hong Kong or mainland China.

Against a backdrop of the 2014 Umbrella movement and 2019 anti-extradition bill protest, China’s decision to enact national security legislation in Hong Kong, in Beijing’s eyes, is totally justifiable. The reason is because such protest activities, according to the Chinese government, involved ‘separatists’ committing criminal offences against national security, and foreign powers plotting to destabilise mainland China. The democracy activists, for example, actively lobbied the passing of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act by the US Congress to support the democratic aspirations of the people of Hong Kong in May 2019. Therefore, this new national security law, in the words of Zhang Xiaoming, deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council, will be like ‘installing anti-virus software into Hong Kong, with “One Country, Two Systems” running more safely, smoothly and enduringly’.

But notwithstanding the endorsement by Hong Kong and Chinese government officials, irreparable damage has already been done to academic freedom in Hong Kong since the new national security law’s adoption five months ago. Five casualties can be identified here. The first casualty is the American Political Science Association (APSA)’s decision to relocate the workshop “Contentious Politics and its Repercussions in Asia” from Hong Kong to Seoul, South Korea in January 2021, citing concerns about ‘the imposition of the Hong Kong National Security Law and the potential for this legislation to limit free academic inquiry and exchange’. While it has already become all but impossible to organise conferences in Hong Kong on ‘taboo topics’ such as Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet, this move by APSA is a visible sign of a wider and general unease and concern about the sweeping national security law, which many academics fear could spell the end of Hong Kong as a regional hub of academic exchanges and educational quality. The fact that the Vice Chancellors of five publicly-funded Hong Kong universities issuing a joint statement endorsing China’s decision to impose draconian national security legislation on Hong Kong has called Hong Kong’s reputation for academic freedom and excellence further into question.

The second casualty is the University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s firing of Benny Tai, who serves as an Associate Professor of law and a co-founder of the 2014 Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) campaign, in late July. By voting 18 to 2 in favour of removing a tenure-track faculty member, the HKU Council goes against its previous ruling, which said that there were insufficient grounds for his dismissal. While the university senate said it had observed ‘stringent due process’, the move was welcomed by the Hong Kong Liaison Office (Beijing’s main representation in the city), as the pro-democracy activist’s sacking was praised as ‘[just] an act of punishing evil, promoting good and conforming to the people’s will’. The fact that a veteran Professor can be dismissed from his tenured position has prompted Professor Tai to conclude that ‘[a]cademic institutions in Hong Kong cannot protect their members from internal and outside interferences’ because ‘academic staff in education institutions in Hong Kong are no longer free to make controversial statements’.

The third casualty is the implementation requirement of national security law in university campuses issued by the Hong Kong government in October. Under the new law, universities are required to step up promotion of national security education. The Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has recently made it clear that the Secretary for Education would meet with presidents of Hong Kong’s universities to discuss plans to ensure compliance with national security regulations. The law enforcement agencies, according to Lam, could step in if the universities are unable to implement the national security requirement in campuses. With Beijing's leaders viewing Hong Kong’s education system as the main contributing factor leading to the emergence of ‘black-clad rioters’ (a term used by pro-government media to describe the pro-democracy protesters) in the 2019 anti-extradition bill protests, it is not entirely surprising that China would move to tame Hong Kong’s open campus culture of academic exchange through instilling more ‘patriotic’ education and ensuring the obedience of the new national security law.

The fourth casualty, perhaps most profoundly, is HKU governing council’s appointment of two mainland Chinese professors, Max Shen Zuojun and Gong Peng, as vice-presidents of research and of academic development. Both scholars hold positions at Tsinghua University in China and the University of California (UC), Berkeley. Yet, the fact that one of them was until recently listed as a committee member of the Chinese Communist Party has triggered fear (and anger) among students and alumni groups of HKU that the Hong Kong government and the Chinese Communist Party are taking control of Hong Kong’s oldest and most prestigious university. While universities in mainland China are routinely overseen by Chinese Communist Party officials, the appointment of Shen and Gong will, for the first time, mark that members with obvious political affiliations playing vital roles in HKU’s senior management. With Hong Kong’s universities being the constant targets of criticism for being the spearhead of pro-democracy protests, it stands to reason that Beijing attempts to remake universities in Hong Kong in its image under the new national security law.

The fifth casualty is the arrest of eight people (including students, social workers and district councilors) in connection to a peaceful demonstration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in November. While students initially protested the university’s decision to move graduation ceremonies online, some displayed flags that read ‘Hong Kong, the only way out’ and ‘Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times’. Along with being arrested for unlawful assembly, at least three of them were also arrested for inciting secession under the new national security law. The fact that this is the second-largest group of coordinated arrests being conducted by National Security Department (NS Department) of the Hong Kong Police Force has raised some eyebrows. Amnesty International Hong Kong’s Programme Manager Lam Cho Ming, for example, suggested the arrests were a blatant attack on human rights: ‘Chanting political slogans, singing songs and waving flags should never be crimes’, but there is a grim predictability about these arrests that lays bare the deterioration of human rights in Hong Kong since the national security law was enacted’. Indeed, the CUHK’s own staff union and other faculty were also astounded by the university’s decision to call the police in response to a student protest on the university campus, as it was tantamount to creating new speech crimes to crush dissent.

Therefore, despite Beijing’s claims that the new security law would improve Hong Kong’s legal system and bring more stability, the five casualties identified above have eroded the values of academic excellence, institutional autonomy, academic freedom and free inquiry in Hong Kong’s universities. The immediate consequence is teachers, researchers and students are being constantly fearful of mistakenly overstepping invisible ‘red lines’, thereby making it very difficult (if not impossible) for them to teach, study and research freely without fear of government interference or restriction. Rather than being an example of academic freedom with Chinese characteristics, a more logical conclusion is that China’s unilateral imposition of the new national security law on Hong Kong has accelerated the obliteration of academic freedom in Hong Kong’s universities.