26 August 2020, NIICE Commentary 5885

Dr. Pfokrelo Kapesa

Geopolitics is essentially the use of geography to the service or interest of nations/states. The concept and understanding of geopolitics has undergone major changes since the end of the Second World War. Geopolitics today is understood as the ‘expansion of influence’ rather than the territorial expansion as understood in the early twentieth century. Two modern definitions of geopolitics are particularly relevant here. Peter Jay (1979) in his article Regionalism as Geopolitics defines geopolitics as “the art and process of managing global rivalry”. Equally interesting and relevant is the definition by Peter Taylor (1985) in his book Political Geography, where he defines geopolitics as “rivalry in the core for the domination of the periphery by imperialism”.

In the light of the above two definitions of geopolitics, this article is an attempt to read into India’s troubled Northeast through the lens of geopolitical rivalry between India and China.

Northeast India is a triangular shaped area sandwiched between Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar/ Burma and Bangladesh. With more than 98 percent of its territory as international borderland, Northeast India is one of the most important geopolitical regions for India. Connected to mainland India by the 21-km. Siliguri corridor, also known as the Chicken’s Neck, it is known as India’s gateway to Southeast Asia. However, the question remains on why a region with such geopolitical significance is underdeveloped, further defined by a troubled history and with no roadmap to a peaceful future. The article attempts to answer this question through the lens of India-China geopolitical rivalry.

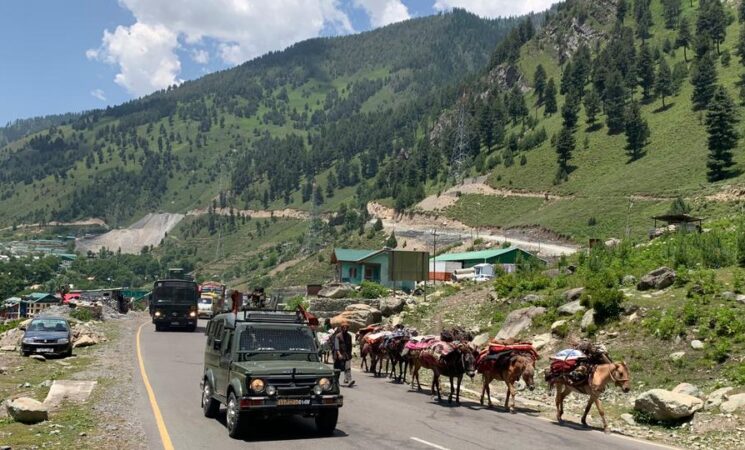

Northeast India has been a highly militarized zone because of its geostrategic location. During World War II, Northeast India was part of the “frontline between the Allies and the Japanese Empire, which had invaded through Burma into Manipur and Nagaland, the Indian troops which fought under the British remained after partition”. More troops were permanently stationed in the region after 1962 Indo-China War. India-China border history has not been exactly peaceful mired by skirmishes and the ghost of 1962 Sino-India war continue to haunt Indian public and policy-makers alike. Again in 1971 Indo-Pakistan War, also known as Bangladeshi War of Independence, “India hosted Bengali guerrilla camps in support of Bangladeshi independence from Pakistan” in the region. The rise of nationalist movements in region further increased the stationing of troops both to suppress the movements and police the international borders between China, Burma and Bangladesh.

One of the most recent conflicts in the region is the issue of water security and environmental disaster. The Chinese projects of diverting the waters of Brahmaputra along the border have left a fear of environmental disaster in the region.

India has expressed serious concerns over China’s projects on the Brahmaputra and the Chief Minister of Assam recently warned that attempts to divert the waters of the Brahmaputra would result in environmental disaster and a negative impact on the local economy of the state. The Indian side has its own list of mega hydro projects in the region. Northeast India has witnessed a constant link between new Hydro Electric Project (HEP) and new deployments of Indian paramilitaries which are “ostensibly a response to the build-up of Chinese forces and bases on the other side of the border”.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which is in force in the States of Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, except Imphal Municipal area, three districts namely Tirap, Changlang and Longding of Arunachal Pradesh, and the areas falling within the jurisdiction of the eight police stations in the districts of Arunachal Pradesh, is by far the largest contributor to the stationing of armed forces personnel in the region.

Could the heavy deployment of troops in Northeast India under the guise of law and order problem be motivated by geopolitical reasons? Despite an impressive size of army and weapons, troop movements have always been Indian military’s biggest weakness.

The existence or the creation of ‘disturbed areas’ can thus be considered part of a strategic game plan, a part of the military preparedness for any eventuality. In this age, a full-fledged war between two nuclear powers India and China is most unlikely. However, low intensity conflicts and border skirmishes will continue. The recent border incursions are ample indications that a strong and ready force on the borders is a necessity for both sides. A demonstration of ‘toughness and resolve’ is necessary and perhaps the most logical step to address both the adversaries and domestic constituency for both sides.

Commenting on the responses after the border incursions, Rajesh Basrur in his RSIS commentary categorically pointed out that President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi both “populist strongmen under domestic pressure arising from the twin crises of COVID-19 and economic turbulence, are involved in a game of “chicken” that neither would want to ‘lose’ by swerving away from a major clash”. Against this background, the perfect opportunity for New Delhi to strengthen its position vis-à-vis China is by increasing the military build-up in Northeast India.

For a country that boast of harmony and democratic ethos, such build-up are justified in the name of national security. The existence of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) was a ‘fix all’ solution to maintaining a large troop in the region. To the domestic audience, the stationing of troops in the region is justified for the breakdown of ‘law and order’ in the region; to the international community (China), India has a standing force in the region.

The level of violence and political turmoil in Northeast India have largely been submerged or suppressed in most cases. The Naga militant/political movement and the instability thereof is as important, if not more, to the Indian State as it is for the Nagas as this provide the perfect cover to station troops. The continuance of Naga political/militant movement has no end in sight as indicated by recent rounds of talk between India and the Naga political/insurgent groups. The continuance of the conflict, therefore ensured Indian strategic and military options and choices because of its geographical location. Thus, the troubled history of Northeast India can largely be contributed by the India-China geopolitical rivalry.