03 August 2025, NIICE Commentary 11539

Dr. Jiyaul Haque

Climate change and unplanned urbanisation are reshaping the social, ecological, and infrastructural fabric of rapidly growing towns in India. Rising temperatures, erratic weather patterns, and deteriorating air quality are no longer limited to metropolitan cities. They are increasingly affecting Tier-3 cities that were once considered climatically stable and ecologically rich.

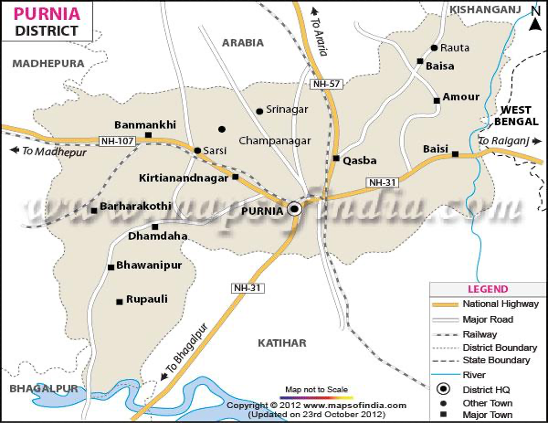

Purnia, the fourth largest city in Bihar and an emerging economic hub, exemplifies this concerning trend. Situated between the Kosi and Saura rivers, this town was once named Mini Darjeeling for its pleasant weather, abundant orchards, open grazing fields, and water bodies. However, it has undergone rapid and unplanned urbanisation over the past two decades.

Image: Official map of Purnia

As a native of Purnia, I have not only witnessed these changes but also experienced the growing discomfort. Increasing traffic congestion, worsening air quality, shrinking green cover, rising temperatures, declining rainfall, depleting groundwater, and unpredictable weather patterns have become regular features of urban life.

Urban expansion, Remittances, and Shrinking Green Spaces

Purnia's transformation can be predominantly attributed to the influx of the rural population driven by aspirations for better education and healthcare. This migration has been enabled by rising incomes, particularly through remittances from family members working in other regions of India or abroad. Thus, many rural people in the Purnia division have experienced improved household earnings, leading to greater mobility and demand for urban housing and services.

This demographic shift is evident in the Census 2011 report, which shows that the city's population rose to 343,005, which is 10.51% of the district's population, up from 6.2% in 2001. Between 2001 and 2011, the city's population surged by 54% and is estimated to cross 455,000 by 2025. However, this rapid urbanisation has not been accompanied by adequate planning. Open spaces that once served as grazing fields or play areas have been replaced by concrete structures. Mango and litchi orchards have vanished. Traditional rainwater routes have been blocked. What used to be a breathable town has become increasingly suffocated by dust, noise, heat waves, and traffic.

A reflection on Then and Now

When I reflect on my secondary school days in the early 2000s, Purnia seems like another world. During monsoons, it would rain for five or six days straight that transformed every open space into shimmering ponds alive with fish. We often rushed outside to swim, enjoying catching colourful fish and putting them in a glass jar. Even during storms, we found comfort in nearby orchards, collecting fallen mangoes. The roads were quiet and garbage-free, and the air was clean and fresh. Even the open drains were once pollution-free and home to thriving fish in shallow waters. I still remember municipal workers coming to clean the drains and catch fish hidden in the mud.

Today, this vibrant world seems like a distant memory. The drains are now choked with filth. Summers are unbearably hot, and rain floods the streets. Unchecked traffic, pollution, and lack of green cover are not only inconveniences but also indicators of a deeper urban crisis.

In June 2025, I returned home from Delhi to visit my family. One afternoon, I went to Line Bazar, the city's medical hub, to buy a cervical pillow for my mother-in-law. What should have been a simple errand became a harsh reminder of how drastically my hometown had changed.

The sun was scorching, the streets were barren of shade, and the widened roads cleared of trees offered no relief to the pedestrians. The newly expanded spaces, intended to ease movement, were occupied by parked vehicles and roadside stalls. I struggled to find a place to park my bike as each store I approached was surrounded by vehicles left by patients and caregivers from across the region seeking treatment. Eventually, I found a distant spot to park and bought pillows.

On my return, I got stuck in traffic for over an hour, drenched in sweat and dust, with honking horns all around. I have never felt the sun so punishing in my hometown. Ironically, though Delhi is often hotter, I suffered more in Purnia, a chilling sign of how quickly the climate and urban experience deteriorated.

The unequal face of Climate Change

Climate change affects everyone, but not equally. Wealthier households in Purnia have responded by installing air conditioners, water purifiers, and relying on private healthcare. Meanwhile, poor families suffer longer power cuts, face worsening heat, and are more exposed to dust and health risks without the means to mitigate them.

The surge in air conditioning has strained power grids, leading to frequent power outages that further affect lower-income households unable to afford inverters or generators. Additionally, increased temperature and dust cause serious health challenges to the poor, especially those whose livelihood depends on physical work, such as labourers, rickshaw pullers, and street vendors. Thus, climate vulnerability exposes the poor to greater risks and deepens existing socio-economic disparities.

A Call for Sustainable Urbanisation and Policy Alignment

The challenges faced by Purnia are not unique. Many Tier 3 cities are expanding across India, often without sustainable master plans. As highlighted in the 2023 UN-Habitat report, cities undergoing rapid growth face inadequate infrastructure, reduced green space, poor waste management, and fragmented governance.

These trends match what is unfolding in Purnia, and if not addressed, will snowball into larger crises affecting millions of people. While India already has national and state-level climate policies, particularly the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), which provides a strong framework for promoting integrated urban planning, green infrastructure, and efficient climate adaptation, the real challenge lies in their implementation at the ground level. Limited awareness, gaps in institutional capacity, and a lack of coordination among various agencies hinder meaningful action. It is time to empower local governance with resources, trained personnel, and stronger inter-agency coordination to implement this policy effectively.

Dr Jiyaul Haque, a specialist in Development Studies, holds a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi.