21 August 2020, NIICE Commentary 5849

Dr. Anand V.

With the passage of two decades of the twenty-first century, the global balance of power is seen to be undergoing a flux, the most notable feature of which is the growing US-China rivalry on the technology front. China’s emergent Science and Technology (S&T) prowess has fuelled US’ concerns about the former’s efforts to undermine the latter’s global dominance by leveraging technology. The dual-use nature of the technologies pursued as well as its access to the military, effectively guaranteed by China’s distinctively insecure political system, has been the basis for such concerns. Space capability is an important marker of a country’s S&T standing. The Space Race was an important feature of the Cold War, in addition to the Arms Race and the ideological competition. At a time where there is a growing discourse on the emergence of a New Cold War, it therefore becomes imperative to gain more insights into China’s S&T trajectory by assessing its space programme.

China’s Fall from Grace and its Revival: The S&T Dimension

China was one of the leaders of S&T in the ancient world. China’s civilizational complexity, partly marked by its advanced S&T at the time, helped identify itself as superior to the crude, nomadic cultures of Inner Asia as well as a template to be adopted by its neighbours in East Asia. In its multi-millennial existence as a civilization as well as an empire, China has pioneered various technologies which are commonly used in the contemporary world – from the mundane to the strategic. Subsequently, stagnation crept in after China’s empire reached its imperial peak during the Qing dynasty and the simultaneous establishment of European colonialism over Asia, powered by the industrial revolution. The result was China’s “Century of Humiliation” which followed, spanning the Opium Wars and the Chinese Civil War, during which the nation lost control over its destiny. Regression in the S&T domain and the neglect over its advances elsewhere were identified as key reasons for China’s downfall.

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) under the Communist Party of China (CPC), efforts were made to rebuild and boost China’s S&T sector. However, the Maoist excesses played spoilsport over such revival multiple times. Nevertheless, with the return of stability and a cautious openness to the world during the Deng Xiaoping era, the S&T sector found fertile ground to flourish. The Four Modernizations, which aimed at radical progress in S&T along with agriculture, industry and national defence, became instrumental for China’s rise in this regard. Subsequently, party leaders trained in S&T streams were promoted to the highest levels, the effect of which was visible in China’s civilian and military development in the twenty-first century.

Following the consolidation of S&T field, efforts to gain leadership over global S&T advances became prominent. China also started efforts to reverse the brain drain and bring back Chinese origin professionals from the West through its “Thousand Talents” programme in 2008. Initiatives like “Make in China 2025”, “Internet Plus Action Plan” and the “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan”, as well as numerous S&T roadmaps and development plans were introduced to further this larger goal. China has been emphasizing of late on a transition from merely being the “factory of the world” to becoming the world’s leader in technology. It seems that by making rapid advances in the key S&T areas like outer space, China is seeking to gain back its place under the Sun.

China’s Tryst with Space Technology

The outer space sector in China is one of the most significant components of its S&T matrix. Ancient China’s four great inventions are well known – papermaking, printing press, gunpowder and compass. The field of rocketry has been a spinoff from China’s invention of the gunpowder, even though its military value was understood quite late in China’s long history of innovation. Apparently, there was a fatal attempt at human spaceflight in the Ming dynasty era by an inventor named Wan Hu, by strapping rockets onto his chair. Moreover, there is the mythical story of a Chinese goddess who flew to the Moon, after whom China’s current lunar exploration project has been named after. The historical and cultural roots of spacefaring in China are, therefore, noticeable.

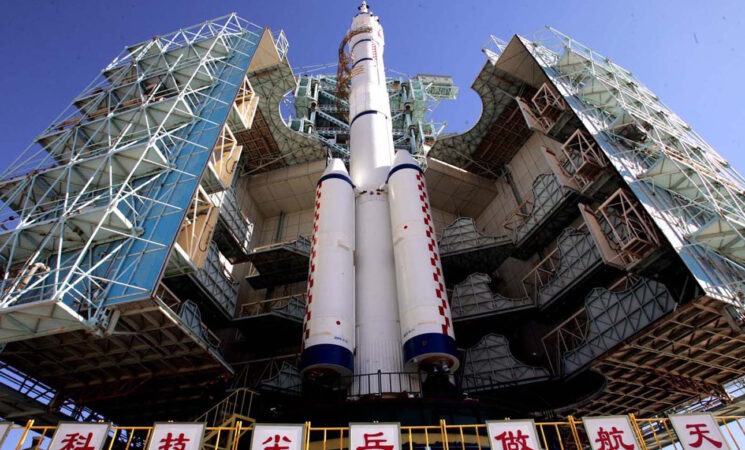

After Mao consolidated the CPC rule over modern China, he put emphasis on developing the country’s strategic programme in response to the US nuclear blackmail during the Korean War and the Taiwan Strait Crises. The satellite programme was an offshoot of China’s strategic programme. China’s ballistic missiles belonging to the Dong Feng series, developed as part of its strategic programme, were used as templates for building up a fleet of Chang Zheng (Long March) launch vehicles. The space programme of China evolved largely as an independent effort, with only the initial technological knowhow gained from the Soviet Union, as well as the Chinese origin, US trained, scientists and engineers like Qian Xuesen who were welcomed back to China by Mao Zedong. These developments took place at a challenging time as China turned antagonistic towards Soviet Union and immersed itself into the turbulence of Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, China launched its first satellite, the Dong Fang Hong-1 in 1970, becoming the fourth country to do so.

The Catch-Up Game

China was well behind the technological curve when it entered the orbit, and by the time its space activities gained momentum, the Space Race was over, with the USA and Soviet Union hardly leaving out any significant first achievements for others. Moreover, by the mid-1990s, the US stopped any sort of technological co-operation with China in outer space domain due to espionage concerns, and was also kept out of the prestigious International Space Station (ISS) project. By the turn of the Twenty first century, China expanded the profile of its space programme by aiming for human spaceflight through its Shenzhou programme. China sent its first human to orbit in 2003, the only third country to do so independently, establishing itself among the league of major spacefaring nations.

By 2007, China became the third country to conduct Anti-Satellite Test, showcasing its ability and intent to protect its space assets as well as target adversarial ones, and gaining the label of a space power. Within a couple of years, China also launched its first Moon mission, the Chang’E-1. Subsequently, China became the third country to soft land on the Moon in 2013 with its Chang’E-3. By the end of the first decade of the Twenty-first century, China started catching up with the US and Russia in terms of the number of annual launches. By 2018, it surpassed both the countries by launching 38 satellites. Currently, China is only second to the USA in the number of active satellites in orbit. At the same time, the decade saw China pushing ahead its space station plans. China deployed its Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2 space station prototypes in 2011 and 2016, respectively. Currently, China is planning to start construction of its space station, the Tianhe so that it could be operational in orbit by the time the ISS expires. In that case, the Tianhe will become the sole manned outpost to exist in orbit, giving China a unique stature in outer space.

China has also been launching new satellite constellations with advanced capabilities in the remote sensing, communication and navigation applications. China completed the construction and commissioning of its Global Satellite Navigation System (GNSS) called Beidou in mid-2020. With this, China became part of an elite club of nations having its own operational GNSS capability, the others being the US (Global Positioning System or GPS), Russia (GLONASS) and European Union (Galileo). The Beidou was started in the mid-1990s after China witnessed the GPS powered US winning the Persian Gulf War. Moreover, China realized that it needs to develop such a system indigenously, when the US withdrew its GPS support to the country during the Taiwan Strait Crisis, leading to China losing control over the missiles it had fired. Thus, China’s Beidou and Tianhe projects could be seen as responses for its humiliation at the hands of the US on the GPS and ISS, respectively. Thus, in addition to adding to national power, the S&T advances in China also bear the stamp of national pride, as the CPC authorities keep propagating the “Never Forget National Humiliation” narrative among its citizens.

The Quest for Primacy

At the same time as China made its effect felt quantitatively, it also started to work towards creating a qualitative impact on space technology, which will place it on the path to ‘superpowerdom’ in space. In 2016, China launched the first satellite in the world which could enable hack proof communication using quantum encryption – the quantum communication satellite named Micius. This was perhaps the first time that China unveiled a completely new technology of a game changing potential. In 2019, China landed its Chang’E-4 rover mission on the less known far side of the moon, a technologically demanding task which was never accomplished before by any nation. This highlights the innovative dimensions in China’s space programme, which has been developed in sync which the country’s larger S&T policy.

Along with innovation also comes the aspect of risk taking. China has moved away from risk-averse satellite projects and has ventured into high risk areas in space technology like human spaceflight and deep space exploration. China has also discarded its geostrategic cautiousness in placing strategic infrastructure on the coast, by operationalizing its first sea facing satellite launch centre in Hainan Island within the past decade. Such qualitative and quantitative trends highlight the nature of the trajectory China’s S&T capabilities are likely to take – a path in pursuit of primacy. However, questions remain as to how much China’s current political system could enable the development of a critical level of innovation, which underpins the disruption needed for a power shift in the global stage.