28 October 2024, NIICE Commentary 9686

Anant Mishra & Prof. Christian Kaunert

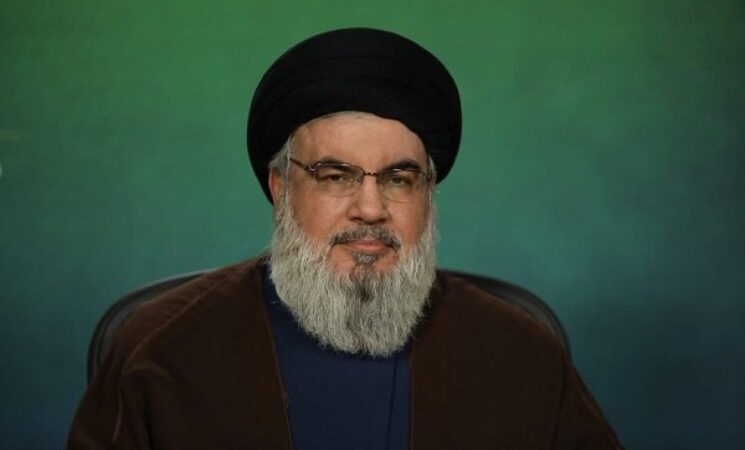

As more than two weeks have passed since the death of Hassan Nasrallah, political groups around the world, especially those in South Asia and some in Latin America, continue to express solidarity and ‘adjust’ to the new reality, a colossal loss of this highly revered ‘political leader’. To the folks in Islamabad, this revered politico-religious leader was simply exceptional, committed not just to the Lebanese people, but demonstrated firm resolve against the Israeli military might, setting an example of justice and integrity while inspiring millions all across the world. As these words resonate sentiments of local Pakistanis towards Nasrallah during their interview with the authors, some frantically disagreed with the slain leader’s decision on Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian conflict. Nonetheless, most remembered his dedication and commitment to the Lebanese people (and his resolve against Israel); one local maulvi remembered his ‘selfless devotion’ and strong will to unify the Muslim world in the cause of Palestinian liberation. One Karachi-based scholar remembered his contribution towards uplifting the marginalised communities inside Lebanon, which resulted in the unification of Lebanese society. The scholar further hailed Nasrallah for the Israeli defeat in 2006. This elevated respect for Hezbollah, making it the most effective deterrent against Israeli offensives in the region.

From the authors’ mentioned above interviews, it is clear that Hassan Nasrallah’s death is ‘still mourned’ by the masses of the Global South. To be precise, outside Lebanon (let’s say the Middle East) from Malaysia to Venezuela, millions may have wept after learning of the Hezbollah leader’s death. The authors opine that one country most agonised by Nasrallah’s death is Pakistan. That said, the anguish appears to grow, but at a slow pace. Those grieving expect some compassionate response from the civil-military oriented regime in Islamabad. According to one scholar, the streets of Islamabad and Lahore witnessed scenes of grieving women and children – who (before Nasrallah’s death) were demonstrating almost daily, inciting slogans against Israel, making the view surreal. The numbers, in the first few days post-Nasrallah’s death, appeared to grow from the regular count of protestors chanting slogans for Palestinian solidarity, demonstrating against Israeli military action in Gaza and Lebanon. This view is all the more surreal, taking into account Islamabad’s tendency to systematically repress all calls/actions for solidarity. This means that the military leaders in Islamabad have chosen to silently displease their masters in the West. What is more appalling (from the perspective of local Pakistanis) is their sheer acceptance of or probable infusion with the growing sectarianism within society. On that note, the followers of Mohammad Bin Salman (the office of the crown prince in conjunction with the house of Al Saud) took years, if not decades, to instil anti-Iran/anti-Shi’a sentiments within the Kingdom. Putting disastrous consequences arising from such propaganda aside, staunch followers of erstwhile Prime Minister Imran Khan proudly walked the streets of Lahore, chanting slogans to celebrate the ‘glorious life’ of the slain Hezbollah chief, openly advocating for more Hassan Nasrallah’s to join the fight against Israel. The number of Pakistanis rallying after his death was already more than expected, a wave of sentiments brought thousands onto the streets of Lahore to celebrate Tehran’s retaliation inside Israel, enthusiastically chanting pro-Iran slogans to celebrate ‘victory’. One journalist opined that the winds of Pakistani sentiment not only reached the house of Al Saud but also the Pakistani military hierarchy, which, according to him, were enraged. It remains unclear whether the Saudi family reached out to the Pakistani politico-military leadership via diplomatic channels – but the latter’s failure to suppress emotions towards Iran’s Axis was definitely heard in the Middle East. In the author’s interview with the journalist who spoke to three different confidants of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, local Pakistanis’ support for the two political leaders (Ismail Haniyeh and Hassan Nasrallah) echoed the sentiments carried by Imran Khan, mirroring his commitment to the people of Pakistan, who continues to resist against the current dispensation to this day. Taking purely sentiments into account, the Pakistanis’ commitment to support Imran Khan echoes their desire to look for a Haniyeh or Nasrallah, with some hailing his tenacity to defy the current dispensation and his fight for the people of Pakistan. But, the authors argue, is this sentiment enough to calculate the change in the fabric of Pakistan’s society? It is without a doubt that the politico-military regime in Pakistan is quickly losing legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The biggest point of discontent, even within the political elites, is the current regime’s decision to bring about such a constitutional amendment that undermines the Supreme Court. According to one journalist, local Pakistanis view this as the regime’s efforts to create a ‘kangaroo court’ formulated by political leaders working under the influence of the Pakistani military hierarchy. This sheer interference in an already questioned/largely criticised judiciary has enraged the young tech-friendly youth, mirroring the spark from Imran Khan’s defiance.

Not Iran; China is an all-weather ally.

As Pakistan’s society slowly drifts its sympathies towards Iran, the military hierarchy continues to echo its strong commitment to the US, with the intent to receive IMF loans on generous terms, preventing the country from dipping into economic collapse. But, like all elites, these loans, one journalist argues, vanish into the pockets of rich Pakistani oligarchs. With Pakistan’s society most affected by the exponential growth in inflation and unemployment, the regime appears to have knocked on the doors of Beijing again. According to one former Pakistani public official, Beijing was recently requested to resettle the timeline for loans while providing some more to prevent any further dip in its economy. With a new regime in place, one scholar argues, Pakistan’s economy continues to dip even after being the flag bearer of Beijing’s much-hyped projects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and its flagship, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

With the killing of Chinese nationals on a steady rise, the politico-military hierarchy has no choice but to make all sorts of promises to Beijing in the hope it stands firm with its “all-weather ally.” The economic situation in Pakistan is so dire, one scholar opines, that the military establishment in Islamabad even discussed surrendering the port of Gwadar to Beijing, giving them the option to host Chinese naval assets permanently. It remains unclear whether Islamabad has discussed such an option with Beijing or if the latter will accept it in light of its recent advisory to their citizens on not visiting Pakistan.

In that context, witnessing a change in the sheer fabric of Pakistan’s society, with local masses from all walks of life have the name of Hassan Nasrallah on the tips of their tongues since his death. With a history of the Pakistani armed forces (not just in Lahore and Islamabad but elsewhere) ruthlessly suppressing all calls of solidarity, their apparent decision to distance themselves from such an action this time reflects a change of heart in the politico-military hierarchy, resulting in their decision not to disperse such large gatherings chanting pro-Iran slogans. The root cause of hesitation can perhaps be found in Pakistan’s social media, which is loaded with expressions of solidarity for Ismail Haniyeh, Hassan Nasrallah, and Imran Khan among pro-ISI terror factions (termed as freedom fighters), with recruitment videos showcasing their fight against Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

The decision also reflects some pragmatism from Islamabad’s politico-military hierarchy, which may have finally accepted the mess as theirs, witnessing winds of change in the nation’s political space and choosing not to confront this unparalleled scenario. This also means the political class could refrain from deterring these 'winds of change' in key federal regions, prohibiting smaller provinces from being influenced. This means that, in provinces bordering India, armed forces may violently suppress anti-genocidal protests. But the question arises: for how long?

It is also important to note that Pakistan continues to witness serious direct military confrontation from actors such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), undermining Islamabad’s ability to protect its territorial integrity. This has resulted in a sustained information campaign conducted by groups such as the TTP, slowly diminishing Islamabad’s efforts, which simply terms it as meagre ‘recruitment propaganda’ – which steadily seeps into the very fabric of Pakistan’s society. The members of Pakistan’s elite continue to rule from a high horse, refusing to concede even against the sheer will of the people. This appears to have unified the followers and non-followers of Imran Khan alike, fuelling a fight to push politico-military leaders in Islamabad into a corner, not so long from now. Taking the decision not to disperse the crowd points towards the sheer reluctance of Islamabad’s politico-military hierarchy to douse the fire, which could potentially engulf the state months (if not years) from now.

Local Pakistanis appear to take resolve from the people of Gaza or Lebanon, finding hope in the ideologues of militant leaders like Haniyeh or Nasrallah. Talking to the local Pakistanis’ reflect their sheer desire to look for a Haniyeh or Nasrallah who would lead their fight on the streets against Islamabad’s political elites, drawing from the sheer courage of the people of Gaza or Beirut, uniting all walks of life against Islamabad’s political elites, who continue to deny two meals a day to their own people.

Anant Mishra is a visiting fellow at the International Centre for Policing and Security at the University of South Wales, UK. Prof. Christian Kaunert is a Professor of International Security at Dublin City University, Ireland and Professor of Policing and Security at the University of South Wales, UK.