5 July 2023, NIICE Commentary 8675

Shaik Sharief

As India set its sights on becoming a Vishwa Guru (global leader), questions started to raise on the nation's strategic culture, particularly in military and foreign policy. The contention lies in the perceived lack of a systematic approach to strategic thinking in India, prompting a discourse on the untapped potential of centuries-old knowledge and its divergent opinions and interpretations. India's strategic thinking is shaped by its rich history, diverse culture, civilization, and geographical location. From the ancient era of Kautilya and Ashoka to the modern times of Nehru and Modi, India has developed a unique strategic culture that reflects its identity, geopolitical interests, and security challenges.

India's strategic culture is not a monolithic entity, but a composite one that differs from the Western one regarding its views on society, politics and statehood. “Strategic culture is that set of shared beliefs, assumptions, and modes of behaviour derived from common experiences and accepted narratives (both oral and written), that shape collective identity and relationships to other groups, and which determine appropriate ends and means for achieving security objectives.” Scholars and analysts have presented conflicting assessments of India's strategic thinking, indicating that strategic culture is not uniform worldwide. For example, a 1992 study by John Tanham, conducted for the Pentagon, suggested a "relative lack of strategic thinking" in India. However, a 2006 Pentagon-commissioned study argued that India possessed an original tradition of strategic thinking stemming from ancient texts like the Arthashastra. The misconception that India lacks a robust strategic culture may arise from its oral culture, unlike the book cultures of the Chinese, Greeks, and Judeo-Christian traditions in the West.

Ancient Period

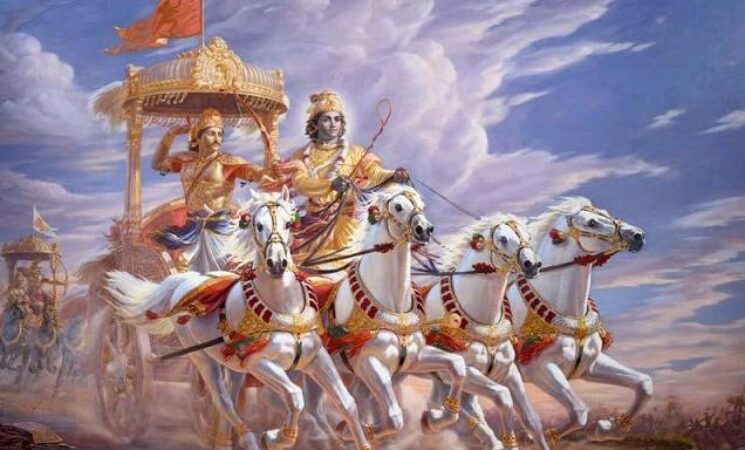

Ancient Indian strategic culture drew from important literary texts like the Mahabharata, Panchatantra and Kautilya’s Arthashastra. The Mahabharata told the tale of a war between the Pandavas and Kauravas, offering insights on a virtuous king's responsibilities in defense, war, administration, policy, and people's happiness. The Panchatantra, composed around 3rd century BC, is a collection of fables where animals serve as characters. These stories spread worldwide and taught statecraft, strategy, alliances, espionage, morality, and power to princes.

Kautilya's Arthashastra stands as the most influential source of India's strategic culture, serving as a comprehensive treatise on statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy. Its discovery in 1909 had a profound impact, presenting a systematic and extensive exploration of governance, administration, law, finance, trade, agriculture, industry, defence, foreign policy, espionage, welfare, and ethics. Similar to Niccolo Machiavelli's 'The Prince,' it explores monarchical statecraft, realpolitik, and the practices of war and peace. The Arthashastra introduces the Mandala Theory, explaining geopolitical relations among neighboring states based on power and proximity. It defines Shakti (power) as the ultimate objective of statecraft, providing means to acquire and sustain it, aligning with a hardcore Realist perspective.

In addition to the realist tradition, an 'idealist' tradition is evident in Indian statecraft, originating from figures like Buddha and Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. Renouncing war, they embraced a peaceful foreign policy emphasizing cultural diplomacy. These ancient traditions highlight principles of peaceful coexistence, conflict resolution, and 'moralpolitik.'

Medieval and Modern Period

Foreign invasions, colonial control, and independence movements all influenced India's strategic culture. From the 11th to the 18th century, Muslim dynasties brought new political ideas, military organization, gunpowder, feudalism, and Sufism to India. These influences integrated into Indian culture, art, architecture, and music, fostering a syncretic and pluralistic society. Meanwhile, naval power grew with the Marathas and Cholas, leaving a lasting impact on Southeast Asia.

The arrival of European powers, Dutch, French, and the British, brought about a new era of domination in the name of trade. The British East India Company gradually transitioned into the British Raj, exercising Diwani rights (political and economic control) over regions such as Orissa, Bihar, and Bengal through the acquisition. The 200-year British rule introduced several changes to India including liberalism, democracy, nationalism, a bureaucratic system, English education, and railways. Some sections of society adopted these ideas, while others rejected. Indian soldiers made significant contributions in World War I, earning recognition from British generals. Their achievements can be attributed to a rich history of warfighting and traditions of statecraft and military strategy passed down through generations in India.

Under British rule, India witnessed the rise of nationalist movements led by figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, Subhash Chandra Bose, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Bhagat Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The movements for Indian independence had varying approaches, including societal reform, non-violence, constitutionalism, revolution, resistance, radicalism, communalism, and nationalism. These diverse strategies shaped India's strategic culture, embodying realism, idealism, pragmatism, militancy, unity, and diversity.

Contemporary India

India's contemporary strategic culture is best understood through the influence of three founding fathers: Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel, and Jawaharlal Nehru. Gandhi represents idealism, Patel embodies realism, and Nehru combines Kautilyan realism with idealistic principles. This unique blend of political realism and idealism characterizes India's strategic culture. Other factors shaping India's strategic culture include its historical legacy, cultural diversity, partition violence, global aspirations, and the contributions of intellectual figures like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. Figures like C. Rajamohan, P.V. Narasimha Rao, Manmohan Singh, Narendra Modi, and S. Jaishankar have also played significant roles in shaping India's strategic culture.

As indicated by its unwavering commitment to non-alignment, opposition to racial discrimination, pursuit of strategic autonomy, adherence to a No-First-Use policy and Credible Minimum Deterrence, and advocacy for decolonization, India's strategic culture stands distinct from Western concepts. These principles highlight India's dedication to nuclear disarmament and its desire to be a responsible global actor. With Narendra Modi coming to power in 2014, there is a shift from Defensive realism to offensive realism, a definite departure from the Nehruvian framework of Non-alignment and Strategic autonomy.

India's strategic culture reflects its rich history and resilience amid a changing global order. Drawing from ancient epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, as well as influential works like Kautilya's treatise, India's strategic thinking has evolved over centuries. Foreign invasions, colonial rule, and the struggle for independence have deeply influenced its strategic outlook. India's assimilation of diverse cultural and political ideas has fostered a syncretic and pluralistic society, shaping its strategic culture.

The changing geopolitical landscape of a multipolar world forces India's strategic culture to adapt and evolve. While Western concepts are considered in policy formulation, they do not replace India's unique strategic culture. India's ability to navigate covert wars, address border security, and forge favourable foreign relations is rooted in its rich tradition of strategic thought. This robust strategic culture guides its actions. India strives to preserve its unique identity while embracing global influences, aspiring to become a global leader, known as Vishwaguru.

Shaik Sharief is a Research Intern at NIICE.