25 March 2023, NIICE Commentary 8580

Angshuman Konwar

It is quite visible that the global order is changing rapidly. The unipolar world hegemony that the United States enjoyed for over three decades (after the collapse of Soviet Union) is now being challenged by multiple forces like Russia, India and other global organizations like the BRICS which aspire to have more of a say in international issues. However, if there’s one country that is really challenging the hegemony of the United States, it is none other than China. With the latest push for its image as a reliable, trustworthy “Global Superpower”, China is upping its game by throwing its hat into the ring of being recognized as a global peace-making or peace-brokering entity.

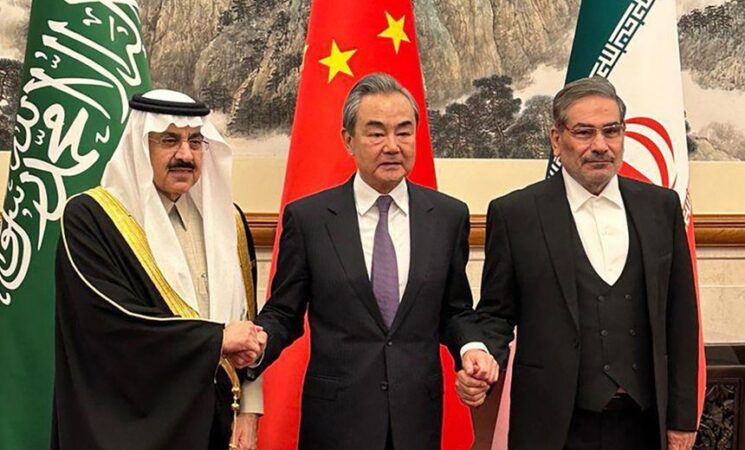

Superpower competition is almost always characterized as a danger to global peace and prosperity. But occasionally, geopolitical rivalry can enforce great powers to do some good. In early March of 2023, Iran and Saudi Arabia, long at odds with each other, announced that they would resume diplomatic relations in a deal brokered by China. The accord to end the seven-year estrangement between Saudi Arabia and Iran was delivered at a time when the US President Joe Biden’s Middle East team was focused on restoring Saudi-Israeli relations. The normalization agreement that Riyadh and Tehran signed is significant not only because of its potential benefits for the region-but also because of China’s leading role, and the United States’ absence, in the diplomacy that led to it.

The surprise agreement has major ramifications for Washington’s efforts to contain Iran’s nuclear program and for its already strained relations with Riyadh. Yet, China’s involvement in the transaction may have the greatest and most significant long-term effects. Beijing reached a conclusion with the two Middle Eastern rivals through a rare diplomatic mission outside of its own country and such diplomatic endeavors are likely to become more frequent in the future. Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to reopen embassies and reestablish diplomatic ties within two months after four days of talks in Beijing, according to a joint statement from the three countries. Old security cooperation and commercial agreements were resurrected as the two nations reaffirmed their mutual respect for each other’s sovereignty and commitment to refraining from meddling in one another’s internal affairs. The Iran-Saudi agreement represents a diplomatic victory for China and it may signal the beginning of a Chinese foreign policy trend in which Beijing engages in more active diplomacy in areas where it has previously exercised minimal influence.

This kind of diplomacy is not unique to West Asia. With the extended Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is eyeing greater influence in those areas where the United States seems to be paying less attention. For example, China’s infrastructure-led approach offers an alternative to the mainstream Western model for development and peace in Africa. France is reviewing its relationships with African countries and the US has arguably lost its dominant position in Africa. This paves the way for China to play an even more prominent role in African peace and security.

With its desire of being perceived as a dependable, authentic peace-broker in the region and beyond, China hopes to mediate a peace deal in the ongoing Ukraine-Russia crisis. Beijing’s relationship with Moscow is at its peak and is quite evident to all, giving Beijing a clear advantage over Washington in this mediation. Wang Yi, China’s top foreign policy official, stressed the need for peace talks at the Munich Security Conference in February before a stop in Moscow. He used language that appeared aimed at peeling European nations away from the United States. He suggested that Washington wanted the war to continue to further weaken Russia. “Some forces might not want to see peace talks materialize,” he said. “They don’t care about the life and death of Ukrainians or the harms of Europe. They might have strategic goals larger than Ukraine itself. This warfare must not continue.”

But China’s 12-point statement did not go over well in Europe. And many European officials, like their Ukrainian and American counterparts, are convinced that early talks on a peace settlement will be at the expense of Ukrainian sovereignty. Similarly, it would be interesting to observe how the Iran-Saudi deal pans out in the coming days and whether Tehran or Riyadh will really be able to hold their end of the bargain.

This new image of China, however, is not without contradictions. With its frequent violations of Taiwanese airspace and the mobilization of thousands of troops near the LAC and its consequential periodic border clashes with India, it seems quite ironic on the part of Beijing to be portraying itself as an alternative peace-brokering unit when it is displaying aggressiveness in its immediate neighborhood. It accuses the US of fuelling wars in different regions of the world while it takes pride in having no boots on the ground on any other foreign soil; but its expansionist policies make Beijing look as suspicious as its western counterpart in seeking true peace for the world.

Although a ceasefire and restoration of peace in the Ukraine-Russia crisis is highly appreciated as it would normalize the global food and energy supplies to a great extent, its implementation nonetheless wouldn't be simple and easy. However, if China succeeds in brokering a peace deal between the belligerents it would be a grand diplomatic victory for Beijing; establishing it as a true alternative to the United States overshadowing not only the Iran-Saudi deal, but also other significant deals like the Camp David Accord, Oslo Accord and others that the West and particularly the US is citing to downplay Beijing’s victory achieved in the Middle East recently.

Angshuman Konwar is a Research Intern at NIICE.