7 March 2023, NIICE Commentary 8567

Vaibhav Kullashri

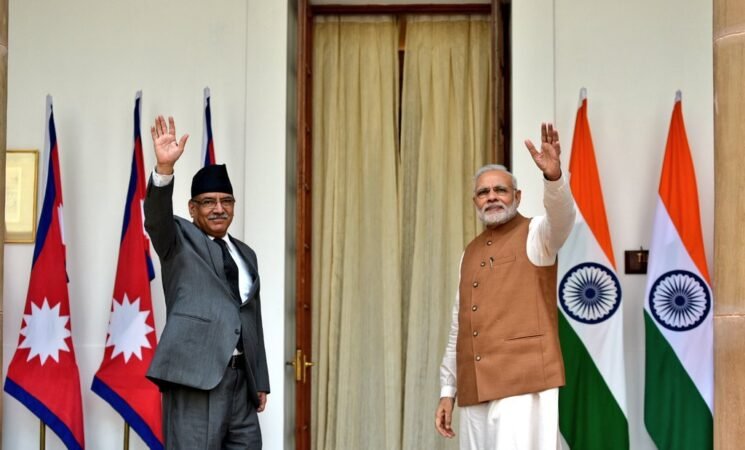

‘India’s Neighbourhood First’ policy has been at the forefront of Modi's foreign policy initiative since he assumed office in May 2014. Orchestrated to improve the relationship, enhance connectivity and boost trade, investment and cultural connections with neighbouring countries for synergic economic development. Though the policy is yet to meet its desired objective due to continued instability in the countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan and Myanmar, it has still managed to project India’s presence as a leading power in the region. However, the mid-course correction and specific policy initiative for specific neighbouring countries under the Neighbourhood First policy is the need of the hour.

Nepal, being landlocked country sandwiched between the two Asian giants, India and China - needs special attention considering the growing hostility between India and China. In this context, the article highlights the importance of Nepal for India and how New Delhi can address the upcoming challenges to enhance the dwindling India-Nepal relationship.

The India-Nepal relationship is unique and symbolises the inherent value of Hinduism, i.e., Vasudev Kutumbakam and peaceful co-existence. Open borders, people-to-people connectivity, and shared cultural, social and religious linkage stand out and integrate the people of two great nations. Nothing in totality exists between India and Nepal; everything is shared, thereby holding a shared identity. Economic statistics may indicate Nepal’s dependence on India; however, considering current geopolitics in the region and growing China’s presence, New Delhi needs Kathmandu much more. In contrast, Kathmandu’s interest in leveraging China is based on its commitment to providing its citizen's jobs, education and health facilities. At the same time, New Delhi’s interest lies in minimising the Chinese presence to avoid confrontation in mutual competition. Chinese presence in Nepal does not irk India’s policymakers, but the threat perception of the possible use of Nepal’s territory against India is where the problem lies.

New Delhi’s limitation to economically respond on a scale compared to Beijing makes it appear that relationships between India and Nepal are on a downslide. However, considering the historical linkage, the relationship is robust and will stand the test of time. Nevertheless, New Delhi needs to do the mid-course correction in its policy initiative towards Nepal rather than the other way around. First, New Delhi needs to view Nepal as a 'friend' and not as a 'brother'. Friendship happens on mutual terms, while brother may differ based on individual capability. Undoubtedly, Nepal cannot match the size and scale of India; thereby, the mutual friendship gives Kathmandu a sense of sovereignty and identity, which Nepal deserves. Therefore, despite having the best intentions, India’s efforts are often not appreciated by the general public as they find India’s attitude as a big brother rather than as a friend. Second, New Delhi must be more inclusive to Nepal while projecting its soft power. Indian values like Yog, Puran, Vedas and Buddhism are common to both the country and when these soft powers are casted as Indian origin, it irks the Nepali public. PM Oli's comment that 'Lord Ram was born in India and real Ayodhya lies in Nepal' reflects this very perception that is being built over time. The Nepali public wanted to keep the historic ties with New Delhi but at the same time wanted its identity to be respected on the same line as that of India.

Third, India must shed its twin-track approach in dealing with its neighbour, especially Nepal. India must support the government of the day and keep itself from affiliating to any political party and ideology, although propagation of the idea of democracy must be carried forward. India’s policy must be based on the national and security interest of the country and not on the political interest, especially in the neighbourhood. Any instability in neighbouring countries trickles down to neighbouring states of India and challenge India’s internal security. Nepal shares a long land boundary with India and a buffer state with China.

Fourth, India needs to correct its policy initiative to allow Nepal’s neighbouring states like Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Sikkim, to interact directly with Nepal, as mentioned by Ambassador Rajit Rae in his book Kathmandu Dilemma: Resetting India-Nepal Ties. Such an initiative will certainly ease out the border tension and enhance people’s cooperation across the border.

Fifth, India must keep away from siding with any political party and address all the political parties with equal intensity. Choosing or siding with any political party harms the long-term national interest and reflects short-sightedness of the policymakers. Middling into the internal politics by India provide enough space for China to play against India and enhancing its footprint in the nation, which once signed a Friendship treaty with India.

The exponential China rise has undoubtedly put pressure on India’s approach toward its neighbour. The growing needs and aspirations of the young population drive the 21st century. Thereby, seeing economic cooperation between Nepal and China through the prism of the China card is a delusion to the changing geo-economic situation of the region. India must accept the changing reality; however, it must keep its option available to remain relevant in Nepal politics and emotionally connected to the Nepali heart. The centrality and future of India’s neighbourhood First policy lie in the future trajectory of the India -Nepal relationship. Nourishing relations with Nepal must be the priority for Indian policymakers.

Vaibhav Kullashri is Visiting Fellow at NIICE.