12 January 2023, NIICE Commentary 8476

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, Jerome C. Glenn and Josh Bowes

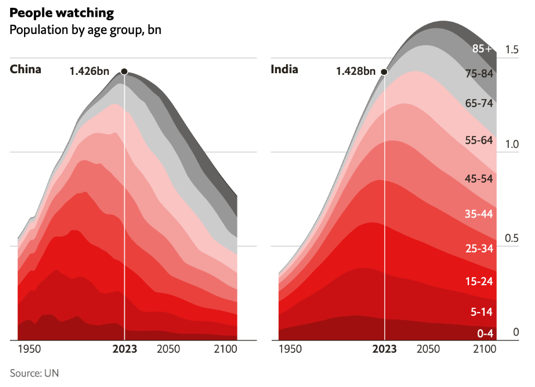

As India’s population of 1.428 billion will pass China’s 1.426 billion this April 2023 (see graph), perceptions toward India and China will change. India’s strong regional leadership and growing economy - will it become a world leader acting like many others throughout history playing zero-sum geopolitical power competitions? Or could it lead to the transition from zero-sum power games to future forms of synergetic relations? If the world continues to play zero-sum power geopolitics, it seems continuing wars in one form or another is inevitable for our future.

Synergetic Thinking

Synergy is a concept made popular by futurist R. Buckminster (Bucky) Fuller. He would say that if you put a wheel in a box, then you don’t get much, but put it under the box, and you get a wheelbarrow to get plenty of work done. Hence, it is not the parts that may be synergetic but rather their relationship. And it is not that the wheel cooperates with the box. Instead, the synergetic relationship creates a new entity with properties not easily predicted by the parts. What synergetic relationships between Taiwan, China, and the US are possible? What synergetic relationships could be created between India and the United States or China? Could a recovering Sri Lanka work with India to develop international synergy?

The Millennium Project, a global participatory think tank, has just created the South Asia Foresight Network (SAFN) to do collaborative futures research for the region and explore synergies among these nations. With its ambitious economic and military assistance to the South Asia region, China has become the largest trading partner to many South Asian nations. India’s neighbouring countries have chosen global powers to balance off India’s dominance of the region. The geopolitical tension will be apparent, with India making strong alignments with the US and its Indo-Pacific partners, with the rest of the neighbouring nations aligning with China. While the cross-border issues, maritime security, trade, economic and climate challenges will be at the forefront for many policymakers, it’s essential to find innovative synergetic solutions to move away from the zero-sum mentality. SAFN was born to explore and hopefully identify realistic synergies among South Asian nations.

The Millennium Project, a global participatory think tank, has just created the South Asia Foresight Network (SAFN) to do collaborative futures research for the region and explore synergies among these nations. With its ambitious economic and military assistance to the South Asia region, China has become the largest trading partner to many South Asian nations. India’s neighbouring countries have chosen global powers to balance off India’s dominance of the region. The geopolitical tension will be apparent, with India making strong alignments with the US and its Indo-Pacific partners, with the rest of the neighbouring nations aligning with China. While the cross-border issues, maritime security, trade, economic and climate challenges will be at the forefront for many policymakers, it’s essential to find innovative synergetic solutions to move away from the zero-sum mentality. SAFN was born to explore and hopefully identify realistic synergies among South Asian nations.

Zero-sum Power Game

India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar accused Pakistan of hosting Osama bin Laden and attacking a neighbouring Parliament should not ‘sermonise’ on matters referring to the Kashmir issue at the United Nations Security Council. Reply to this was swift, with the Pakistan Minister for Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Shazia Marri threatening India with nuclear war, reminding New Delhi of Islamabad’s “nuclear status.” The two nuclear powers in South Asia accuse each other, depicting a continuous zero-sum game. Perhaps what is missing is an innovative synergetic application to move away from traditional zero-sum thinking.

The pandemic has disrupted the international political system leaving hefty geopolitical challenges and straining socio-political order across the globe. The impact on the world’s least integrated region, South Asia, has been severe on every front, with disorder and laboured relationships among states. But even as COVID-19 slows down, the region faces an abundance of new challenges. Inflation has crippled food costs in South Asia, worsening food insecurity for millions. Sri Lanka’s ongoing economic crisis saw the country’s highest inflation rate in 2022, resulting from a series of failed harvests and reduced imports of food grains. According to World Bank data, the effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has decimated the global oil supply, increasing the price of crude oil by 15 percent. The cost of essential food has risen dramatically as a result. For many nations like India, Sri Lanka, Maldives and Pakistan, higher oil prices mean higher fertilisation prices and increased transportation costs. Governments in the region use fuel subsidies to better equip consumers with skyrocketing global commodity prices.

Regional Trade

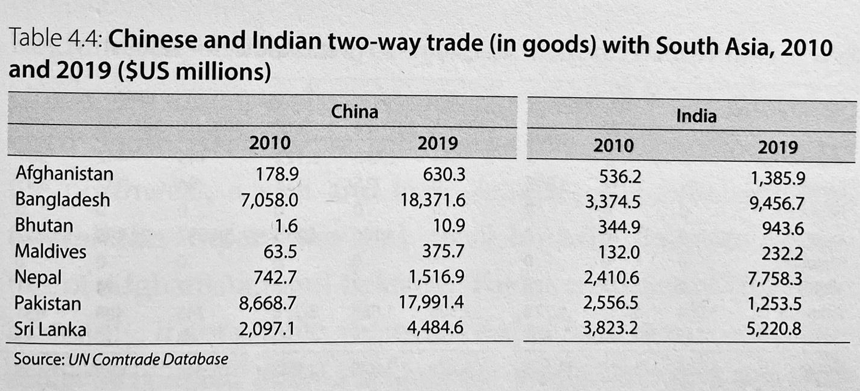

According to Riya Sinha and Niara Sareen from Brookings, South Asia’s ‘protectionist policies, high logistics cost, lack of political will and a broader trust deficit’ has not allowed intra-regional trade in South Asia to exceed 5 percent of the region’s global trade. The South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) has failed to lead to any positive increase in intra-regional trade. Such colossal issues require a multifaceted approach with a diverse array of geopolitical perspectives, yet multilateralism has been dwindling in the age beyond COVID-19. The failure of multilateralism to fully blossom staggers growth in the region and prevents the means to establish a cohesive international security community. The ongoing conflict between India and Pakistan, the role of external states, the intensification of China’s power and influence and escalating nationalism and populism are a handful of significant challenges that are situated in the way of multilateralism. Chinese presence from its economic weight and military power has rapidly expanded - and it was only inevitable. China is now the largest trading partner for many South Asian nations (see Table 4.4) and remains a significant arms supplier to most of these countries (see Table 4.5). The growing Chinese strategic influence, in addition to regional asymmetries among South Asian countries, will further push for conflict in the region.

According to Riya Sinha and Niara Sareen from Brookings, South Asia’s ‘protectionist policies, high logistics cost, lack of political will and a broader trust deficit’ has not allowed intra-regional trade in South Asia to exceed 5 percent of the region’s global trade. The South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) has failed to lead to any positive increase in intra-regional trade. Such colossal issues require a multifaceted approach with a diverse array of geopolitical perspectives, yet multilateralism has been dwindling in the age beyond COVID-19. The failure of multilateralism to fully blossom staggers growth in the region and prevents the means to establish a cohesive international security community. The ongoing conflict between India and Pakistan, the role of external states, the intensification of China’s power and influence and escalating nationalism and populism are a handful of significant challenges that are situated in the way of multilateralism. Chinese presence from its economic weight and military power has rapidly expanded - and it was only inevitable. China is now the largest trading partner for many South Asian nations (see Table 4.4) and remains a significant arms supplier to most of these countries (see Table 4.5). The growing Chinese strategic influence, in addition to regional asymmetries among South Asian countries, will further push for conflict in the region.

South Asia will remain one of the least integrated regions globally, with intra-regional trade making up only a fraction of all trade. The cancellation of 2022’s SAARC foreign minister’s meeting over conflicting views regarding the role of the Taliban is another pointer toward the slow demise of the regional organisation. The inability of SAARC’s members to meet for a summit since November 2014 in Nepal is a testament to a failure of agreement among its nations. One of the primary challenges facing multilateralism is the ongoing geopolitical and territorial disputes. India’s complex relationship with its smaller neighbours means they have long looked for cooperation from extra-regional powers to limit India’s dominance.

South Asia will remain one of the least integrated regions globally, with intra-regional trade making up only a fraction of all trade. The cancellation of 2022’s SAARC foreign minister’s meeting over conflicting views regarding the role of the Taliban is another pointer toward the slow demise of the regional organisation. The inability of SAARC’s members to meet for a summit since November 2014 in Nepal is a testament to a failure of agreement among its nations. One of the primary challenges facing multilateralism is the ongoing geopolitical and territorial disputes. India’s complex relationship with its smaller neighbours means they have long looked for cooperation from extra-regional powers to limit India’s dominance.

Border Disputes

Pakistan-India relations have long been fragile due to the continued land dispute over the Kashmir region. Tensions between Hindus and Muslims resulted in the threat of extremism and terrorism, which has seen an uptick in fringe political and social movements, some of which have erupted in violence. Such events have eclipsed opportunities to address regional issues and the efforts to establish a multilateral order. India has refused to cooperate in SAARC discussions amid Pakistan’s avoidance to assist India in the aftermath of an attack by the Pakistani terrorist organisation Jaish-e-Mohammed on the Indian Army in 2016. As a result, India neglected to attend the 19th SAARC summit in Islamabad.

Pakistan has abstained from participating in regional communication with India and has steered clear of joining any international forums like BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral and Economic Cooperation). India’s far-right populist government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) has created a tense domestic political situation where national security and sovereignty are a higher priority. South Asia has long suffered from extremism and terrorist activities, with many fatalities emerging from ethnic and ideological conflicts, posing a severe threat to stability and security. However, Sri Lanka and Nepal have urged for a renewed SAARC meeting, but India has proven to show no interest.

Regional Security and Terrorism

The region faces a plethora of common challenges, primarily on the security front. Worsening economic conditions across India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nepal, and Afghanistan have proven to spawn breeding grounds for extremist groups, particularly with the Taliban retaking control of the Afghan state. In addition to Modi’s growing power in India amid the country’s rivalry with Pakistan, unrest in Bangladesh over similar nationalistic concerns continue to exasperate an already struggling government. The leader of Jamaat-e-Islami (Bangladesh Islamic Assembly), the country’s largest Muslim party, was recently arrested after joining protests pressing for the resignation of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Security challenges most related to the rise of extremism in South Asia only propagate the worsening of food and water shortages and put already suffering communities into further poverty. The threat of terrorism remains rife in the region, with many Al-Qaeda and ISIL subgroups like the Taliban, Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant - Khorasan (ISIL-K) active and claiming credit for some attacks. Arrests of Bangladeshi terrorists in Kolkata with possible links to Al Qaeda and Harkut-ul-Jihad al-Islami (HuJI) indicate that there are systematic attempts by larger terror groups trying to mobilise in urban areas across the subcontinent. On January 11, 2023, an attack outside the Afghan foreign ministry in Kabul killed several people. Responsibility for the attack was claimed by ISIS-K and potentially targeted a meeting between the Taliban and Chinese officials, affirming the prevalence of terroristic competition in the region and the ever-growing tension between China and its southern neighbours. A working and effective multilateral South Asia would need to prioritise the threat of jihadism and the growing power of terrorist groups. Multilateralism also demands that action is taken to stop state-sponsored groups from gaining power and influence from their host nations. The international community must be efficacious in its efforts to penalise state sponsored terrorism.

The mini-lateral security agreements such as India-Sri Lanka-Maldives are success stories after many years of designing such mechanisms for counter-terrorism, as well as intelligence sharing and security cooperation. These critical areas see less investment from regional nations. Such mini-laterals could be a way forward to achieve multilateralism in the region.

Climate Change

Climate change has obliterated any normalcy in the water cycle of South Asia, resulting in drought in some areas and massive flooding in others. Pakistan’s devastating floods have created a humanitarian crisis, with rain levels increasing by 400 to 500 percent, with more than 30 million were impacted. Concerns over the sincerity of international efforts prevent efforts to combat climate and environmental issues. With more than half of all South Asians, about 750 million people, affected by at least one climate-related disaster in the last two decades, it is imperative that a multilateral view is adopted to prevent the changing climate from exacerbating the conditions of an already poverty-stricken regional population. Increased education on evacuation programs and improved infrastructure must be expanded and made accessible to all people for climate catastrophes to be addressed appropriately. The Bangladesh cyclone warning and shelter program is an example of efficient disaster response and can pave the way for disaster response to improve across the region. South Asia’s urban expansion continues to grow speedily, meaning that proper climate-resilient infrastructure must be developed to combat the changing environment. Increasing community benefits from cost-effective solutions should incentivise regional governments to continue advocating for an aggressive stance against climate change in order to properly serve its people and prevent the spread of disease. A multipronged regional approach is required to support the vulnerable countries of climate change. Maritime pollution is another area that has directly impacted South Asian littorals and Indian Ocean marine life. In 2021, hundreds of tonnes of oil from fuel tanks leaked into the sea, devastating nearby marine life in Sri Lanka. A joint operation was carried out with Indian assistance to minimise the damage; thus, the long-term implication to the environment was considerable. There is a tendency of non-traditional security cooperation in the environment to sometimes have unexpected traditional security outcomes. The “2004 Indian Ocean tsunami laid the foundation for the QUAD, a grouping whose “free and open” approach is contrasted with that of China” argues Nilanthi Samaranayake from CNAS. Further explaining “the strategic competition between major powers calls into question to what extent the cooperation we have seen previously may be possible in the Indian Ocean in the future”.

The existing regional blocs have not shown enough strength to make tangible progress. The overshadowing of domestic political disputes has demonstrated that regional tensions continue to flare, with little to show that multilateralism may be reached. The future of a multilateral order in South Asia rests on a strong and unified attempt to break free of border. disputes and ethnic conflict. The dramatic differences in internal affairs and domestic politics between India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, primarily but not excluding Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, are significant obstacles that require a concerted effort to amend. It is imperative that states find synergetic solutions to prioritise the pressing issues of climate change and regional security for effective and progressive multilateral agreements to come to full fruition. Perhaps a regional disaster management centre could be erected in hopes that South Asian states will initiate a multinational response to natural disasters. Improvements in cross-border infrastructure, such as Integrated Check-Posts (ICPs), road, air and rail links, are vital to improving regional trade. With countries in the region facing strikingly similar challenges, it is crucial that leaders recognise opportunities for alignment to take charge of a progressive and mutually beneficial agenda. Collective leadership must outweigh protectionist attitudes to fit more effectively into the regional and international systems, and there must be a solid effort to revive SAARC for increased regional cooperation. These synergetic solutions will facilitate a changing attitude from pessimistic to optimistic and will allow an increased chance for multilateralism to succeed.

It should be a priority for South Asian nations to bridge the growing asymmetries by working on long-term synergies from informal networks such as the South Asia Foresight Network, dedicated to finding synergetic thinking beyond the present ‘zero sum’ thinking.

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is a Senior Fellow/Executive Director at South Asia Foresight Network (SAFN), Jerome C.Glenn is the co-founder/CEO of Millennium Project, Josh Bowes is a Research Assistant at SAFN.