26 October 2022, NIICE Commentary 8354

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera

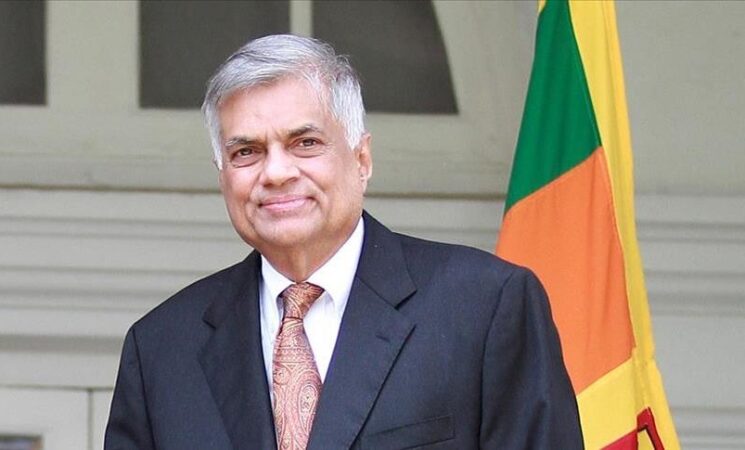

At a celebration of India’s 75 years of independence in Colombo, Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremasinghe highlighted the importance of free trade agreements (FTAs) as a bond between both countries. “The first step,” he said, was “to revive and upgrade the Indo-Lanka FTA into a comprehensive economic and technological partnership. The FTA-related work which started in 2018 and 2019 has not found much progress.” A multilateral path had once looked possible during his tenure as Prime Minister, in 2018. But it stalled, incompatible with the ultranationalism of the now-deposed Rajapaksa government.

Now President Wickremasinghe is making up for a lost time, attempting to revive an economy in serious crisis. In another positive remark towards India, this time on the topic of the Colombo Security Conclave, Wickremasinghe acknowledged that his northern neighbour was central to a conflict-free Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Notably, he promised not to lead Sri Lanka into any power bloc that threatened India.

US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Donald Lu met with Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe. Lu observes “With economic stability, I think will come political stability,”. In Sri Lanka, present political instability has many other contributory factors than the economy, such as rampant corruption, absence of rule of law and geopolitical context.

Opening toward Asia

These overtures are a little surprising. Weeks before those last declarations, Wickremasinghe had invited a Chinese spy ship into Sri Lankan waters, in disregard for Indian reservations. Now he speaks of turning Sri Lanka away from China and working with India towards an IOR security architecture. Perhaps Wickremasinghe was quick to understand that Chinese economic assistance will be simply too thin to help, due to the Chinese economy slowing down to a 3.5 percent GDP expansion. If Chinese growth keeps slowing in the coming years, it will hamper Beijing’s capacity to project power in nations like Sri Lanka.

But beyond pure pragmatism, Wickremasinghe – unlike the ousted Rajapaksa clan, who controlled major ministries for years – knows that China’s state-led model was never superior to Western liberal democracy. He has said so for years, even before such attitudes were convenient.

The Rajapaksa’s have never squandered convenience for something as trifling as political integrity. They are a tribe of survivors. They understand the sordid games and clever deals that make up political power and do not disguise their contempt for public opinion. This kind of Machiavellian obsession comes at a price: the Rajapaksa’s are riven with internal, personal feuds, which ended up costing them their oligarchy. Wickremasinghe, the new leader in Sri Lanka, has followed them with Sisyphus’ patience, constantly frustrated, his eyes fixed on the President’s chair.

The connection between Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Wickremasinghe was captured well by Washington Post journalists Gerry Shih and Hafeel Farisz. “On May 12, 2022, an embattled and isolated Gotabaya named a new prime minister: Ranil Wickremesinghe, the man he secretly met within 2018 when he first jockeyed for the position against his brother.” The secret meeting revealed by the Post came during the constitutional crisis in October 2018. The “constitutional crisis erupted when Sirisena, then President, fired his Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, and replaced him with Mahinda Rajapaksa, whom he had defeated at the polls just three years earlier. Fearing Mahinda trying to outflank him and engineer their own return to power, Gotabaya secretly met Wickremesinghe to pledge his support.” The same Gotabaya -Wickremasinghe connection was revealed to this author the same year, at a Ministry of Defence think tank.

Be that as it may. President Wickremasinghe has still managed to introduce immediate reforms in a few months, more than his predecessor and under grimmer conditions. These reforms, passed with parliamentary consensus, include a preliminary agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a loan of about USD 2.9 billion. The government is looking into value-added tax and liberalization of state industries as well. It’s a good start, but only a start. Debt restructuring will be the next challenge: Sri Lanka owes nearly USD 30 billion. Japan has offered to lead talks with its other main creditors, including India and China; Wickremasinghe’s diplomatic credibility in Japan will be crucial to successful talks.

Domestic Constraints

However optimistic the economic reforms, Sri Lanka’s domestic political constraints have not abated. This is a serious chink in Wickremasinghe’s armour. His poor judgment in domestic politics, particularly his inability to read popular moods, has cost him several elections.

At the moment, his coalition rests uneasily on help from the Rajapaksa’s and the Sri Lankan People’s Front (SLPP). It’s an open question whether this détente will last until the 2024 general election. In the meantime, Wickremasinghe is doing his best to please everyone. He granted Gotabaya Rajapaksa a safe return to Sri Lanka from Thailand. Weeks later, Wickremasinghe expanded the ministerial portfolio from 20 to 37 posts, mostly given to the Rajapaksas’ political supporters. Among these new cabinet ministers are men who previously were accused of human rights violations and serious corruption scandals. This is a dangerous gamble, given the mutinous mood on the island; the combination of a dramatically expanded cabinet, full of political lackeys from the old regime, will likely look worse against a backdrop of hard tax reforms and fiscal austerity. Some of the new portfolios went to the previous regime’s ministers, a recycle of the same process and individuals who caused the current political and economic dysfunction. It's a sign of the Rajapaksa faction’s enduring power, but also Wickremasinghe’s weakness. A back channel installed by the Rajapaksa faction at the highest level of government was, in the end, Wickremasinghe’s choice.

Wickremasinghe Faces the Nation

This whole exercise is a clear disappointment to the protestors and civil society activists who took to the streets for a better political culture. The new leader, who had promised change, simply adopted the autocratic sentiments of his predecessors, and eventually even their personnel. Sri Lanka’s state of emergency was lifted after a few months, once the protest wave subsided. However, a stealth crackdown on the movement’s leaders has now taken place. Wickremasinghe is using the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) to arrest activists, despite vehement objections from international human rights groups.

According to a popular journalist Ranga Jayasuriya, 3,353 activists have been arrested so far, and 1,255 remain in remand custody. Galwewa Siridhamma Thera, an Inter-University Student Federation leader was detained with the IUSF Convener Wasantha Mudalige for more than two months under the PTA. This is a serious rule of law infringement, but worse, the imprisonment of thousands of peaceful protesters on terrorism charges will leave a deep scar on Sri Lankan society, already lacerated by years of terrorism and ethnic conflict. Many civil society activists and groups including medical professionals have condemned these arbitrary arrests, warning the government of grave consequences in the future.

They are quite right. During the civil war, PTA was misused frequently, especially among ethnic minorities. This time the PTA is used mostly against activists from the majority Sinhalese Buddhist community. This presents a serious risk to Sri Lanka’s stability in the months ahead. None of the arrested activists will go through any rehabilitation process; they will emerge from the island’s overcrowded, dysfunctional prisons with an extremist mentality. “Many government goons including parliamentarians and police officers, easily identified on video evidence as attackers of the peaceful protesters, have been enlarged on bail and are roaming freely dispensing their own brand of venom on the people,” News First reported this month.

Is Justice Impossible?

For the first time, a critical UN report on Sri Lanka highlighted the prevalence of economic crime as well as human rights violations. The report discusses the progress of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) under Council resolution 46/1, “Economic crime” was a new addition. The report encourages the international community to support Sri Lanka in its recovery, but also in addressing the underlying causes of the crisis, including impunity for human rights violations and economic crimes. Evidently, the OHCHR hopes that the Wickremasinghe government will respond to the popular demand for accountability for the latter, including corruption, ending impunity and tracing stolen assets. This poses a serious dilemma to Colombo’s new leadership. To take economic crime seriously would mean investigating the Rajapaksa’s and their associates– in other words, breaking Wickremasinghe’s fragile coalition. Even beyond the Rajapaksa’s, the backlog of economic crime is immense including the infamous central bank bond scam, given the history of political interference in Sri Lanka’s judiciary. China, another author of serious corruption in Sri Lanka, would have to be drawn in, threatening to scupper any chance of fair debt resettlement. Wickremasinghe has worked hard on his economic policy prescription. It’s now time to face a domestic challenge long overdue. Wickremasinghe used to be Sisyphus, striving in vain for the presidency; he will have to be Hercules to muck out these Augean stables. The postponed local government elections which will be held next year will give the first indication of people’s acceptance of the Wickremasinghe regime.

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is Visiting Fellow at NIICE.