4 September 2022, NIICE Commentary 8233

Debosmita Sarkar

Transitioning from a LDC to a Developing Country

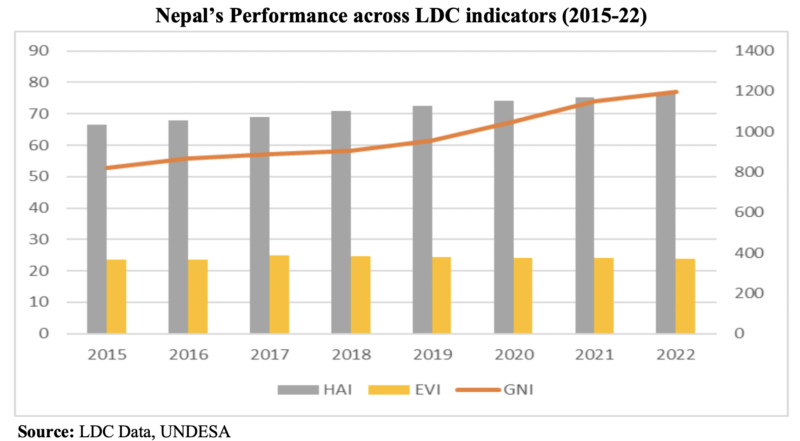

Besides battling the economic fallouts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global aftermath of the Ukraine-Russia war, Nepal is also preparing to graduate from the Least Developed Countries (LDC) category to a developing economy bracket by the year 2026. In the last few years, Nepal has made some progress in addressing its development needs and resilience-building reflected in the per capita gross national income, the Human Assets Index (HAI) and the Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI). The specific support measures to the LDC countries from the international community have aided these advancements to a large extent. However, post its graduation, Nepal is likely to lose access to a host of International Support Measures (ISMs). Currently, while Nepal is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world with a 17 million-workers labour force, it remains heavily dependent on primary sector employment and remittance inflows mostly contributed by millions of unskilled workers primarily in India, the Middle East and East Asia.

Nepal’s Performance across LDC indicators (2015-22)

At this juncture, it has become crucial for the country to invest in domestic capacity building for the most efficient utilisation of its resources - developing sufficient immunity from external shocks, lowering its external sector dependencies and becoming self-reliant to ensure not only a smooth transition to a developing economy, but also ensure the sustainability of this progress in the long-run. Internal capacity enhancement can also provide stronger grounding for Nepal’s foreign policy and economic diplomacy as well - strengthening its regional and international participations. Studies suggest overall progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) over the “Decade of action” can protect the economy against structural vulnerabilities and contribute to higher resilience. In an attempt to resolve its transition conundrum, Nepal must focus on specific sectors such as improving agricultural productivity and non-farm employment, limiting reliance on tourism, and export promotion and diversification, while also catering to inclusive development among its people.

At this juncture, it has become crucial for the country to invest in domestic capacity building for the most efficient utilisation of its resources - developing sufficient immunity from external shocks, lowering its external sector dependencies and becoming self-reliant to ensure not only a smooth transition to a developing economy, but also ensure the sustainability of this progress in the long-run. Internal capacity enhancement can also provide stronger grounding for Nepal’s foreign policy and economic diplomacy as well - strengthening its regional and international participations. Studies suggest overall progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) over the “Decade of action” can protect the economy against structural vulnerabilities and contribute to higher resilience. In an attempt to resolve its transition conundrum, Nepal must focus on specific sectors such as improving agricultural productivity and non-farm employment, limiting reliance on tourism, and export promotion and diversification, while also catering to inclusive development among its people.

Sustainable Development: Assessing Nepal’s Progress

Nepal’s progress along the various SDG targets has been significant since 2015. The country currently ranks 98th out of a total 163 countries, with a 66.2 SDG Index score. While there have been modest improvements in poverty, education, gender equality, sanitation and decent work-related goals in the recent years, major challenges remain with respect to tackling food and nutritional insecurity, universal and quality healthcare access, access to clean and affordable energy, industrial and infrastructure development, economic inequality, rampant urbanisation and overexploitation of its natural capital, particularly its forests. Nepal has performed exceedingly well in some inter-generational equity-related goals through promotion of sustainable consumption and production and effective climate action.

The poverty headcount ratio at USD 1.90/day has been reducing, standing at 6.66 in 2021-22 compared to 7.69 in 2020-21. However, as the country moves out of extreme poverty, a sizable share of its population still survives on daily consumption ranging between USD 1.90/day and USD 3.20/day - extremely vulnerable to relative poverty. Moreover, Nepal experiences one of the highest income inequalities in the world, with an even pronounced wealth inequality - a critical factor contributing to limited development.

With respect to its progress on SDG 5 (Gender Equality), Nepal needs a series of women-centred policies to further improve its female secondary school enrolment rate which currently stands at 63 percent. The government needs to invest in opportunities to absorb educated women into the workforce and leverage it for economic growth. Investments in transport infrastructure can help women access non-farm employment.

As a net importer of food grains, the current climate of international food markets and the inadequate nutritional capabilities of the country present Nepal with significant challenges to ensuring food security, resulting in 36 percent of children under the age of five experiencing stunted growth. On the other hand, reductions in maternal mortality rate, neonatal mortality rate and the under-five mortality rate have been on track hinting towards encouraging results.

While Nepal’s 15th Development Plan has integrated the targets envisioned under the 2030 SDG Agenda, it continues to endure significant gaps in financing and technological support to their implementation, along with other concerns such as SDGs’ localisation, monitoring and evaluation at a granular level. To address these issues, Nepal must prioritise strengthening its socio-economic conditions and develop internal capacities for SDGs implementation, and then effectively leverage its bilateral and multilateral relations to promote regional cooperation in furthering the sustainable development agenda.

Opportunities for Future Growth: Areas in Focus

Nepal’s principle employment sector - agriculture and allied services employs about 66 percent of its total population. Agriculture growth is therefore a prime candidate for furthering economic growth in the country. On the development front, investments in the agriculture sector can simultaneously improve livelihood security for a large section of the population and also address food and nutritional security issues leading to further improvements in SDG 1 and SDG 2. At the same time, a major share of Nepal’s population derives their livelihood from forest ecosystem services. This dependence coupled with climate change-induced risks has prompted significant land use/ land cover change over the last decades. Nepal must incorporate sustainability principles in the management of its natural wealth, embodied in the land resources and flow of ecosystem services to ensure progress along SDG 15 and inclusive growth in the economy.

To reduce external sector dependencies and promote progress along SDG-9, Nepal must expand its industrial sector. Furthering industrial development demands ensuring the availability and retention of semi-skilled and skilled manpower in the country, reductions in establishment costs, expansion of industrial infrastructure, increased production of indigenous industrial raw materials and effective supply chain. These can create an investment friendly environment leading to FDI inflows, diversify the production base of the economy, ease pressure from the agriculture sector and reduce over-reliance on services and the external sector.

Lastly, there is a tendency among Nepal’s youth to migrate to greener pastures abroad (even through illegal means at times). This can only be curtailed by a dual-pronged strategy of upskilling the youth as well as providing them with jobs. To tap into the human capital potential of Nepal, the government must utilise various arenas such as public-private partnerships to deliver quality education to its youth. The service sector needs to incorporate more labour-intensive practices to absorb the increasing number of skilled youths entering the job market every year and avoid brain drain. Simultaneous progress along SDG-4 and SDG-8 can contribute to overall resilience of the economy through most-efficient utilisation of the country’s human capital assets.

The structural hurdles to Nepal’s economic development, such as inefficient natural resource utilisation, lack of quality infrastructure and largely unskilled labour force, currently necessitate growth at a level where environmental impacts are inevitable in the short run-making ‘weak green growth’ ideal for Nepal at this juncture. Lastly, all these developments can strengthen Nepal’s domestic economic conditions substantially and reduce its overall economic dependence on regional partners such as India and China - granting it a stronger foothold in regional forums such as the BIMSTEC, BBIN and the SAARC to negotiate upon its development priorities and actions moving forward.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation India.