25 March 2022, NIICE Commentary 7724

Dr. Ajay Kumar Mishra & Dr. Shraddha Rishi

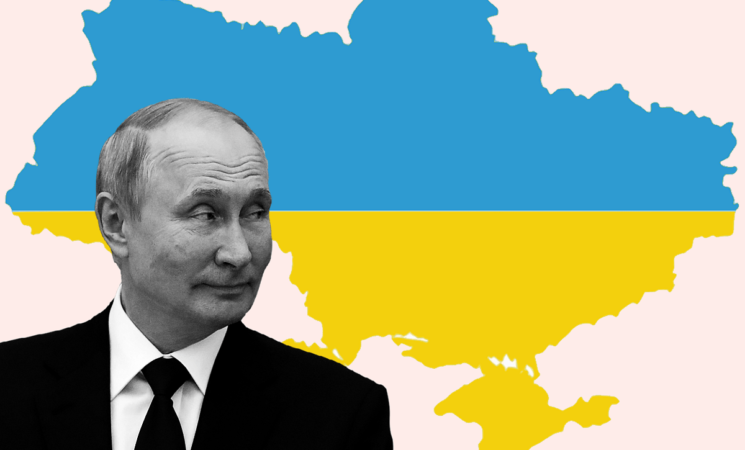

The Constructivist approach can offer a better understanding of the Russian-Ukraine conflict and also offers lessons for South Asia. The social constructivist interpretation suggests that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is based on certain premises. First, Russia perceives Ukraine as an inalienable part of Russia’s history, culture, and spiritual space. Ukraine’s statehood has perpetrated numerous bloody crimes against civilians, including against citizens of the Russian Federation. Second, the Ukrainian oligarchs’-controlled government is planning to acquire nuclear weapons and membership of NATO to threaten Russia. The nature of conflict is based on an ideational structure that asserts ideas and beliefs as the defining elements of the nature of the state in Russia. The present article investigates the nature of the state and its resemblance with the conflicts in South Asia. It examines critically the attempts to ethnicise the state in the region taking lessons from the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Constructivism and Imagined Reality of Nationalism

Constructivism emphasizes the ideational structure rather than material structure as the agent of change. It focuses upon the ideas and beliefs as the main instrument to decide the course of action of states. It entails that reality is always in flux. Agency (ability to act) and structure (international system consisting of ideational and material elements) are mutually constituted. It argues that states can have multiple identities that are socially constructed through interaction with other actors.

The birth of the sovereign states system following the treaties of Westphalia in 1648 has been challenged by social-economic construction in the 19th and 20th centuries to define the nature of the state. Benedict Anderson’s ‘Imagined Communities’ has authoritatively defined nation and nationalism as the emotional bonding to unite the people and make them assertive for the cause of nation and nationalism. It has led to the definition of states on emotional lines such as territory, ethnicity, religion, and language. The case of South Asia is a fine example where the construction of the states has been influenced by emotional appeals. The anti-colonial struggle has given the region a substantial nationalistic outlook along with sub-regional identities based on religion, language, and ethnicity. As a result, South Asia has witnessed the formation of two of its important nation-states Pakistan (on religious line) and Bangladesh (on the linguistic question). It is ethnicism, a social construct, in-state formation with the emergence of right and far-right ruling parties; they define the state in highly nationalistic senses. The term ethnocentrism started in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ethnocentrism is also quite similar to nationalism. All the expressions of ethnocentrism, such as feelings of superiority and even hostility towards out-groups, could be easily attributed to nationalism. Ethnocentric feelings and attitudes such as preference for a familiar culture and group superiority have been exploited by nationalism.

Social Construction of the State in South Asia

The link between strategic communal violence and organic embeddedness is always a tricky one in South Asia. The persecution of Hindus in Pakistan and Bangladesh, Muslims in India, and Tamils in Sri Lanka is a pivotal strand in the mentality that South Asia must be, if not an ethnic state, at least support an ‘ethnic state’. To borrow Martin Luther King’s phrase, South Asia is caught “in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly”. Moreover, the constructivism contradicts anarchical world system propounded by realists and affirms that the world is divided into spheres of influence. It believes that any kind of change depends on the ideas, beliefs, and value system held by states. It emphasises the statism in international relations. The emergence of nationalist and far-nationalist governments based on ethnicism presents an imminent danger to the sovereignty and territorial integrity in the region. The communal embeddedness of the state is reflected in periodic violence in South Asia.

Thucydides, a Greek historian from the 5th century BC, asserts the trinity of fear, honour, and interest as the reasons behind conflict and war. Constructivism based on identity or ethnicity focuses upon honour as the imminent cause to let the conflict prevails. However, South Asia has largely been non-aligned both at the regional and global level thanks to its non-alignment policy that has been motivated by social constructivism of specific socio-economic conditions of the region. Due to non-alignment countries could safeguard their wider developmental interests without getting entangled in power politics. American realist scholar John Mearsheimer in ‘Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault’ in Foreign Affairs in 2014 has opined that “the US and European leaders blundered in attempting to turn Ukraine into a Western stronghold on Russia’s border (p.3)”. Mearsheimer advocates for buffer or non-aligned or neutral status for Ukraine.

Lessons for South Asia

The anti-colonial struggle has been the result of social constructivism to arouse nationalistic sentiments in South Asia. The anti-colonial struggle in such a region having multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-language have affirmed the mindset that carries the idea that uniformity comes at the price of unity, the insistence on conformity destroys the imperative of consensus. It resulted in the conception of unity in diversity that best reflects the social construction of South Asia. Unfortunately, the region could not carry the ethos of anti-colonial struggle and was trapped into conflict caused by increasing statism based on identity and belief. Ethnicism transforms itself into nationalism.

South Asia, as a result, is in danger of facing a crisis of a kind Russia-Ukraine confronts with. Meanwhile, the policy of non-alignment has also weakened in globalisation. The region can take lessons to avoid any kind of such conflicts. First, South Asia must remember that nationalism was regarded with suspicion in the phase of the anti-colonial struggle in the region. Rabindra Nath Tagore had considered it as a malign ideology that is destined to be guided by dominant identity and belief as it is abided by the desire for power. It can lead to the state formation towards uniformity- One Language, One Religion, One Nation. In 2019, the Government of India had passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast tracks citizenship for religiously persecuted minorities (Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis) from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. The decision violates mutual respect of sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the targeted countries. Moreover, it is discriminatory on religious lines as it excludes Muslims of some countries and puts them in a bad light on the front of protection of minority rights. Second, the existence of a networked community in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny, any of the states in South Asia is not immune to ethnic violence taking place anywhere in the region. It is better to employ UN Peacekeeping forces if any gross violation of human rights is noticed in the region. Any state cannot be a party on its own to neutralise the human rights violation in such a networked community where whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. For example, the operations undertaken by the IPKF of the Indian Armed Forces in Sri Lanka were the first of their kind in the history of South Asia. After two years of constant military engagement, the IPKF was withdrawn as it failed to defeat LTTE.

To sum up, the Russia-Ukraine conflict prompts South Asia to respect sovereign jurisdiction and territorial integrity and not to ethnicise the state in the region. It would be Pandora’s box that neither country in the region can afford to open.

Dr. Ajay Kumar Mishra is an Assistant Professor at LN Mithila University, India and Dr. Shraddha Rishi is an Assistant Professor, Magadh University, India.