27 February 2022, NIICE Commentary 7662

Dr. Anmol Mukhia

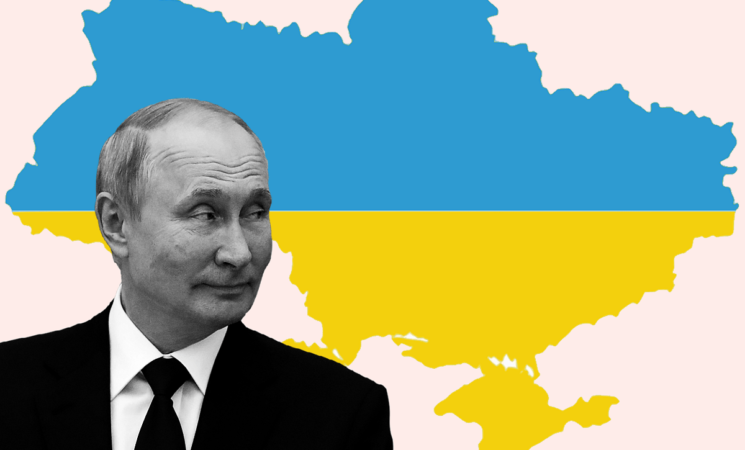

In the era of the 21st century, while choosing friends and allies against adversaries and enemies, perception plays a vital role in dictating state foreign policy. The geopolitical location of Ukraine lies between Russia and Poland. The entire country of Ukraine is divided ethnically and linguistically, with Ukrainian speakers on the west side and the majority of Russian speakers on the east. This demarcates people on the western side of Ukraine as being interested in the European Union vis-à-vis NATO, while the people on the eastern side are not interested in being a part of any of it. The theory of “perception and misperception” in international politics allows multidisciplinary scholars to thoroughly study and discuss the systematic application of cognitive psychology in understanding political decision-makers. The leaders are perceived to deal with certain states based on historical analogy and also fall into the tendency of misperception by overestimating their influence. This response to a “special military operation” in Ukraine is viewed from this psychological perspective, which can be an analytical module in understanding the recent Russian-Ukraine crisis.

Historical link to Crimea

The historical links to the present context of conflict can be traced back to the history of Russia from 1783, with the Tsarist Empire’s annexation of “Crimea” after defeating the Ottoman forces in the Battle of Kozludzha. Following the demise of the Tsar in 1917 and the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922, Crimea was regarded as a sphere of influence. In February 1954, the Soviet government transferred Crimea from the Russian Soviet Federation of Socialist Republics to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. This was led by Nikita Khrushchev to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Ukrainian-Russian unification. Khrushchev himself was a Communist Party leader in Ukraine, who suggested Stalin transfer Crimea to win over the local elites. Crimea had originally been an autonomous republic, but its status was changed to an oblast (province) in 1945. While transferring Crimea to Ukraine on 19 February 1954, the Chairman of the Soviet Union Presidium, Kliment Voroshilov, offered a closing remark as “enemies of Russia had repeatedly tried to take the Crimean peninsula from Russia.” Crimea was a part of Ukraine for 37 years until 1991, when the Soviet Union disintegrated and 15 countries gained independence. The referendum was held in the same year and adopted by the independent Ukraine parliament, which regarded the status of Crimea as an autonomous republic.

Post-Cold War Adversaries: Ukraine, NATO, and Russia

In 1992, relations between newly independent Ukraine and NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) started, and progressively in 2008, when the then President applied for a NATO Membership Action Plan. In response, Russia claims that NATO’s expansion in Eastern Europe violated the agreement. The Warsaw Pact was a collective defense treaty between the Soviet Union and seven satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe, against NATO. It was ideologically opposed to NATO, and this led to an arms race throughout the Cold War. On 25 February 1991, Russia and NATO agreed to call an end to the Warsaw Pact. NATO had promised Russia that once the Warsaw Pact was disbanded, it would not include Eastern European countries betrayed by NATO twice (in 1999 and 2004). In 1999, countries like Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic joined NATO despite Russian opposition. NATO promised no “permanent stationing of substantial combat forces” and “no intention, no plan, and no reason to deploy weapons on the territory of new members.” But the agreement did not help much, as NATO in 1999 started a “war of choice” against Serbia, which was trying to suppress the insurgency in Kosovo. The Kosovo war ended with Russian and NATO forces facing each other at the Pristina airport, where they later settled on the declaration of Kosovo’s independence.

NATO further expanded in 2004 with the seven Central and Eastern European countries, such as Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia, which were under Russian influence. NATO recognizes Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, and Ukraine as aspiring members. Ukraine also has closer ties with the US and NATO influence because it is seen as an aggression which continuously provokes Russia. Russia has made it clear about NATO’s expansion to not be involved in its border area. When it comes to NATO’s summit in Bucharest in April 2008, the end of the summit states, “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO.” We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. The Russian deputy foreign minister said, “Georgia’s and Ukraine’s membership in the alliance is a huge strategic mistake which will have very serious consequences for pan-European security.” Putin himself said, “Georgia and Ukraine becoming members of NATO is a direct threat to Russia.” First, this led to the war between Russia and Georgia in August 2008 as a consequence of it. Secondly, the Russia-Ukraine crisis is a follow-up to the same Bucharest summit.

Crimea and its Importance to Russia

The issue of Crimea was once again seen as of national interest in the era of Vladimir Putin’s leadership. Inside Ukraine in November 2013, former President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to abandon the agreement of greater economic integration with the EU led to massive street protests. This protester was supported by the US, which was seen from the assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasia Affairs, Victoria Nuland’s active visit to Kyiv. Her phone call to US Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt in Kyiv to discuss new favorable leadership in Ukraine was particularly noteworthy. This became public when former President Viktor Yanukovych had to flee the country in February 2014, due to public unrest. Just 16 days after the phone call between Nuland and Pyatt was leaked, Russia started the seizure of Crimea and intervention in Ukraine’s Donbas region. In March 2014, Russia took over the Crimean region, citing the need to protect the rights of Russian citizens and Russian speakers in Crimea. This led to the ethnic division, where pro-Russian separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of eastern Ukraine held a referendum to be independent.

Since the July 2016 NATO Summit in Warsaw, its support for Ukraine is set out in the Comprehensive Assistance Package (CAP). After a year, in June 2017, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted legislation for NATO’s reinstating membership as a strategic foreign and security policy objective. It came into force in 2019 with a corresponding amendment to the Ukraine Constitution under the leadership of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the current President of Ukraine. In September 2020, Zelenskyy approved Ukraine’s membership as a distinctive partnership with NATO, with the aim of its membership as a National Security Strategy. On 21 February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin recognized the separatist-controlled cities of Donetsk and Luhansk as a republic that lies in eastern Ukraine. After three days in the early morning of 24 February 2022, Russia held a full-scale “special military operation” in Ukraine from three sides: the Belarusian border in the North, Donbas in the East, and Crimea in the South.

A Perceived Threat

Many analysts believe that the US is principally responsible for the Ukraine crisis. In the history of international politics, the state has continued to perceive a threat to safeguard its national interest. In the history of US foreign policy, the former president George Bush’s administration perceived Iran, Iraq, and North Korea as an “Axis of Evil.” This perception was based on a nuclear project, and to topple the government, it allowed misperception only to safeguard its vested interest. In his lecture at the University of Chicago Alumni, John Mearsheimer (2015) argued that in the case of Ukraine, the US aimed to peel Ukraine from Russia and this was one of the deep causes. Two institutions are torn apart by Ukraine: the NATO expansion towards Eastern Europe and the EU expansion, which is to integrate Ukraine into the economic grouping. Promoting democracy through the Orange Revolution in Ukraine is to provoke and topple the regime and to find a pro-western regime. For example, former President Viktor Yushchenko desired stable relations with Russia, but his foreign policy prioritized bringing Ukraine towards the West, including NATO and the EU. In his inauguration speech on 24 January 2005, he said, “My goal is Ukraine in a United Europe. Ukraine has a historical chance to discover its potential in Europe. Our national strategy is to move toward our goal boldly, directly, and persistently. European standards are to become the norm of our social life, economy, and politics “.

The process of Ukraine’s step towards NATO membership action plan was closely watched by the Kremlin from time to time. In February 2008, Putin threatened to use nuclear missiles on Ukraine. Ukraine shares borders with NATO members on the south-western side and Russia on the north-eastern side. Russia perceives that Ukraine is seeking its own timeline to join NATO, which is why Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov says, “For us, it’s mandatory to ensure Ukraine never-ever becomes a member of NATO.” President Putin says that if Ukraine joins NATO, the alliance may try to retake Crimea, endangering Russia’s national interests. Thus, Russia is not trying to conquer Ukraine but only wants it to be a buffer state like any other independent state. Russia also does not want Ukraine to become the next NATO member. This is because Russia does not want the West to incorporate Ukraine into the European Union, just like in the Monroe Doctrine, where the US opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. When security considerations are at stake, Ukraine matters to Russia, but not to the West as a balance to be resolved. Giving member status to Ukraine in NATO will also by default abide by Article 5 of the NATO agreement, which will be the bad foreign policy of the US, opening possible nuclear brinksmanship.

Dr. Anmol Mukhia is Research Fellow at National Research University Higher School of Economics, Russia.