26 August 2020, NIICE Commentary 5896

C. Lalremsiami

Since the old high-and-mighty European exclaves gradually draw to dissipate, several countries string out from minor global players. Devalorization of the prestigious Chinese kingdoms during the world war years whereon China suffered a huge relapse, started the ball rolling for the restoration of the Chinese nation. The founding philosophy of restoring China inheres in the revival of Chinese legacy embedded in holding the reins of power. This exclusive determination is purposefully driven by economic and geopolitical motives with political-security enhancement which is well witnessed in China’s policy on the South China Sea.

The supremacy race over the South China Sea appears in the 21st century’s Asia’s most geopolitical disputes. The South China Sea, which is home to diverse islands, islets, atolls, reefs, hydro-carbons, etc. is composed of a multitude significance. Its strategic location, serving as a crucial international sea link for many centuries further enhances the significance of the sea. As such, jurisdictional contestation of the Sea arises between six littoral parties, such as- China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei and Taiwan.

China’s Anticipation in the South China Sea

China is a sea-borne trading nation, and hence, maritime dimensions occupy the nuts and bolts of China’s foreign policy since the early part of the history. The Chinese writers give utterance to the South China Sea as an intrinsic entitlement of successive Chinese dynasties. In its contemporary race of superpower game, China largely formulates grandiose maritime policies pertinent to its economic growth. The South China Sea is such one where China’s myriad dependence on its route remains fundamental. Moreover, an implicit vision on the South China Sea lies at the heart of Chinese leaders thinking owing to the South China Sea occupy a vital cradle of China’s power projection in the region.

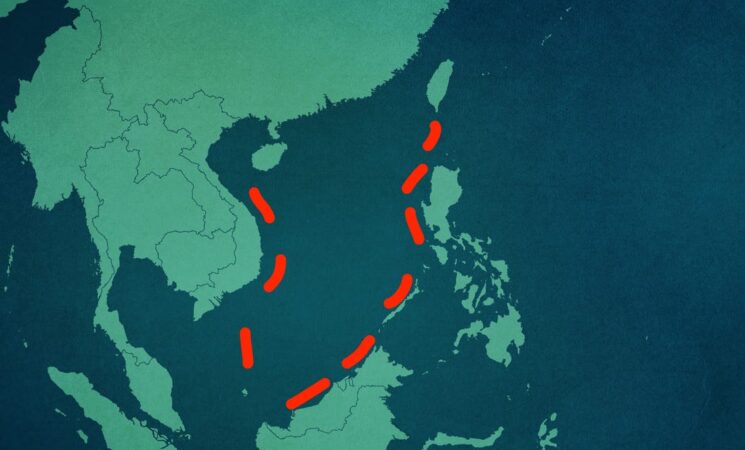

In its move towards legalizing its claims in the South China Sea, the People’s Republic of China produced the official map on the South China Sea called the ‘nine-dash-line’ in 1949. The Chinese Territorial Law 1992, explicitly specify islands of the South China Sea as its exclusive territory. These were the building blocks of China’s unilateral actions in the South China Sea.

China’s Dilemma in the South China Sea

The South Sea or ‘Nanhai’ to Chinese forms numerous significances to the Chinese. China intends to project herself as a formidable sea power which is one of the core aspirations of Chinese leaders since the ancient period. Concurrently, countries of Southeast and East Asia’s economy have been heavily dependent on China’s capital. Hence, China is widely held as an economic shield and geopolitical clout in the region. Keeping this in mind, China wishes to maintain status-quo in the region. This goes well in tandem with Xi Jinping’s dictum called ‘China’s Asian Dream’. Moreover, China, to a considerable extent, has a strong vested interest in dictating the international shipping route as an advantage of its national power.

There is a clear indication that the contending parties of the South China Sea littorals are hooked up in a supremacy squabble. All claimant parties excluding Taiwan had territorial disputes with China and, tiny overlapping claims existed between others. Undoubtedly, the increasing activities of China in the South China Sea have heightened tensions. However, except for some trivial skirmishes ensued between China and other claimant states over the years, deadly pitfalls remain avoided until now. This could possibly be attributed to China’s preponderating maneuver, which it exerts through economic domineering in the region and military leverage in the disputed water. To this end, the weaker nations in the geopolitical game developed fear psychosis in China.

What leaps up the circumstances in the 21st century is the acute circumspection of the non-claimant states. Specifically, the international tribunal ruling on the Philippines case in June 2016 break the silence of the international community and, countries like the USA, India, Australia, and Japan outwardly imposed high-intense pressure on China and urge the conflicting parties to comply with the United Nations Conventions on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS). In the meantime, Chinese Foreign Affairs responding to the international ruling shows China’s accorded precedence of its national law over international law on the South China Sea. Moreover, China prefers to keep the South China Sea dispute away from external power interference, which is a point of divergence with other claimant states. The less-powerful littorals wish internationalization of resolving disputes, while China favors bilateral solutions.

What makes the situation worsen is that, to America, disputes in the South China Sea is not merely a far-flung regional dispute over islands and reefs. The United States is definitely the most prominent country, reluctant to see Beijing led Asia security architecture. As an important step towards this goal, the United States used the South China Sea as a military reconnaissance in the mid-months of this year. China’s unilateral legal order in the South China Sea aggravates the United States and other countries reiterating the significance of maintaining ‘freedom of navigation’ in the South China Sea.

Conclusion

Recent years of development of the South China Sea undeniably witnesses the interface of rising acuity of the external powers and China’s assertiveness of her claims, manifested in the form of a confrontational approach. It is discernible that China exhibits her psychological prowess to the international community. The growing gust of apprehension in the South China Sea dispute essentially appears to be the involvement of external powers which signals that if the situation gets worse, the world might witness the recurrence of Cold-War dilemma in the South China Sea. If such a thing happens, China would have increasing fellow contenders in the South China Sea dispute which could immensely disrupt its national growth. To a great height, the future of the South China Sea conflict places reliance on the actions of China. Nonetheless, the existing situation proves that China will not hold back her claims in the South China Sea. If so, could China still preserve her international status while gaining control in the South China Sea?