24 July 2020, NIICE Commentary 5611

Priyanshi Chauhan

South Asia is undergoing an increase in demand for electricity to sustain the economic growth, and facilitate development, which is outgrowing supply. To address this, initiatives to promote regional trade in electricity like the “SAARC Framework Agreement for Energy Cooperation (Electricity)” were undertaken, and cross-country bilateral interconnections between India-Nepal, India-Bhutan, and India-Bangladesh were established. Despite this, electricity trade in South Asia continues to be limited. This article examines the rationale for regional electricity trade and identifies the challenges considering the institutional, political and economic dimensions.

Trends of Electricity Dependency in South Asia

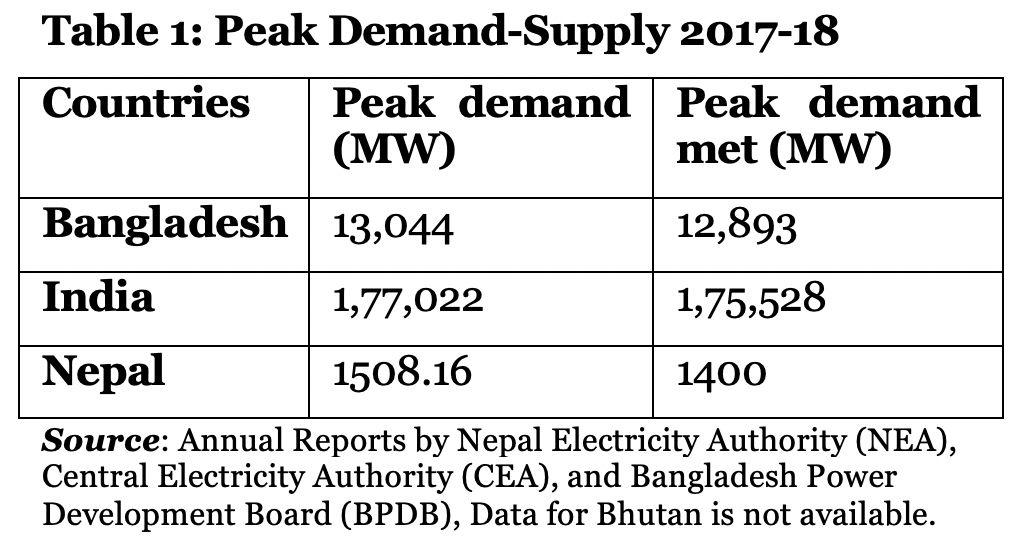

While there is a mismatch between demand and supply of electricity in South Asian countries as shown in Table 1, the country-wise patterns in use of energy resources mostly highlight the dependence on a single energy resource for electricity production. As shown in the figure, natural gas has the highest proportion of energy mix in Bangladesh (76 percent) while coal dominates the energy mix in India (60 percent). Similarly, hydropower has a maximum share in the energy mix of Bhutan (99 percent) and Nepal (93 percent). The existing complementarities in the resource endowments of the countries thus allow for pooling of resources for optimal energy use.

While there is a mismatch between demand and supply of electricity in South Asian countries as shown in Table 1, the country-wise patterns in use of energy resources mostly highlight the dependence on a single energy resource for electricity production. As shown in the figure, natural gas has the highest proportion of energy mix in Bangladesh (76 percent) while coal dominates the energy mix in India (60 percent). Similarly, hydropower has a maximum share in the energy mix of Bhutan (99 percent) and Nepal (93 percent). The existing complementarities in the resource endowments of the countries thus allow for pooling of resources for optimal energy use.

Simultaneously, complementarities exist in the country-wise electricity demand patterns owing to differences in intra-seasonal and peak time differences, and different load curves. For instance, the months of highest electricity demand for Bangladesh and North-Eastern India are different, being April, May and June for the former and July, August, October and November for the latter. Also, the months of highest demand for Bangladesh are the months of low or medium demand for North Eastern India. Similarly, the months of highest peak demand for Northern India, i.e., June-September, are the months of low electricity demand in both Nepal and Bhutan. The diversity and complementarities in resource endowment and demand patterns, therefore, offers opportunities for electricity trade in South Asia. Presently, electricity trade in the region exists only at the bilateral level between India-Nepal, India-Bhutan, and India-Bangladesh. As shown in Table 2, the trends in electricity trade highlight the Indian role as an exporter for Nepal and Bangladesh, while importing electricity from Bhutan.

Simultaneously, complementarities exist in the country-wise electricity demand patterns owing to differences in intra-seasonal and peak time differences, and different load curves. For instance, the months of highest electricity demand for Bangladesh and North-Eastern India are different, being April, May and June for the former and July, August, October and November for the latter. Also, the months of highest demand for Bangladesh are the months of low or medium demand for North Eastern India. Similarly, the months of highest peak demand for Northern India, i.e., June-September, are the months of low electricity demand in both Nepal and Bhutan. The diversity and complementarities in resource endowment and demand patterns, therefore, offers opportunities for electricity trade in South Asia. Presently, electricity trade in the region exists only at the bilateral level between India-Nepal, India-Bhutan, and India-Bangladesh. As shown in Table 2, the trends in electricity trade highlight the Indian role as an exporter for Nepal and Bangladesh, while importing electricity from Bhutan.

Limitations in the Current Setup

At the regional level, the SAARC Framework Agreement for Energy Cooperation (electricity) emphasises on non-discriminatory access to national grids and negotiations on voluntary basis through bilateral, trilateral and regional agreements; and highlights the need for regional institutions for system operations and dispute settlement. Despite the Framework Agreement providing a set of guiding principles, it is only at the initial stages of conceptualisation of the idea of power integration. It is also marked by a lack of future plan for the development of a regional power market and the process for its evolution. There is an absence of regional institutions to monitor, implement and review the development of the South Asian power market. The issues of transmission, and investment are addressed at the national level and are agreed upon in the specific bilateral Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). Furthermore, there is no evidence yet of trade between countries with third party access through the transmission grid of another country. For instance, there is no electricity trade between Nepal and Bangladesh through the Indian transmission grid. In a positive move, the Government of India in 2018 announced the new ‘Guidelines for the import/export of cross border electricity’ to facilitate regional power trading arrangement by allowing Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan to sign tripartite agreement for electricity trade and providing for transmission corridor on the Indian territory. The guidelines are an enabler for regional electricity trading arrangements in South Asia.

Challenges to Cooperation

Despite progress on some fronts, energy cooperation in South Asia has seen only limited success in regional energy cooperation. There have been instances, where projects were cancelled, most evident in the case of Myanmar-Bangladesh-India (MBI) pipeline, owing to the political mistrust and strategic concerns despite economic viability of the project. Furthermore, the issue of high trade deficit raised by Bangladesh then, also highlights the way trade relations affect the political relations of the countries. Even the limited regional integration led to quite rapid and disproportionate increase in Indian exports in the smaller states in the region, therefore, harbouring feelings of deprivation of access to the larger Indian market. This is likely to disrupt regional cooperation due to lack of mutual benefits. In addition, unresolved border issues, and the increasing involvement of China have also adversely affected India’s relations with its neighbours. The differences in standards across technical, regulatory, and policy frameworks, and in the structure and mandate of the regulators in respective countries are additional challenges.

There are constraints at the domestic level too, that impede cross-border trade in electricity. The power sector in the South Asian countries is not completely liberalised and continues to have a significant state regulation. The monopoly market structures do not generate enough finances to invest in the infrastructure for trade and in the expansion of generation capacities required to cater to new markets. The regulations related to tariff settings also affect the ability of electric utilities to attract investment for the creation of cross-border infrastructure. As such, the limited power sector reforms do not offer adequate incentives to the private sector to invest, and makes it difficult for the existing utilities to recover costs. The inability to recover costs leaves the utilities with reduced funds for expanding generation capacities which further reduces the incentives for investment in cross-border trade and investment.

Policy Recommendations

Despite these challenges, a regional arrangement for electricity trade will work in favour for South Asia. A gradual approach should be followed moving from bilateral trade (as it exists), to third party access where trading is possible between any pair of countries using transmission grid of third country in the region, and eventually a multi-player regional competitive market. Further, South Asia should develop a comprehensive policy framework that goes beyond the guiding principles and has detailed provisions for implementation and monitoring, harmonisation of transmission codes and operation system, and dispute settlement. Finally, South Asia should look beyond bilateral tensions, and promote energy cooperation in pursuit of mutual gains for sustained economic growth and sustainable development, which is also likely to promote peace and stability in the region.