3 June 2020, NIICE Commentary 5195

Guncha Prakash

As the world continues to reel under the COVID-19 crisis, China is finding this the opportune time to further flex its muscles in the South China Sea (SCS) with its acts of international law violations, notching up its military presence and preventing the island nations and other countries in the region from drawing the benefits of the ‘high seas’. Considering the ever-evolving global dynamics, more so in the present scenario, the US and Chinese face off in this sea demands some attention.

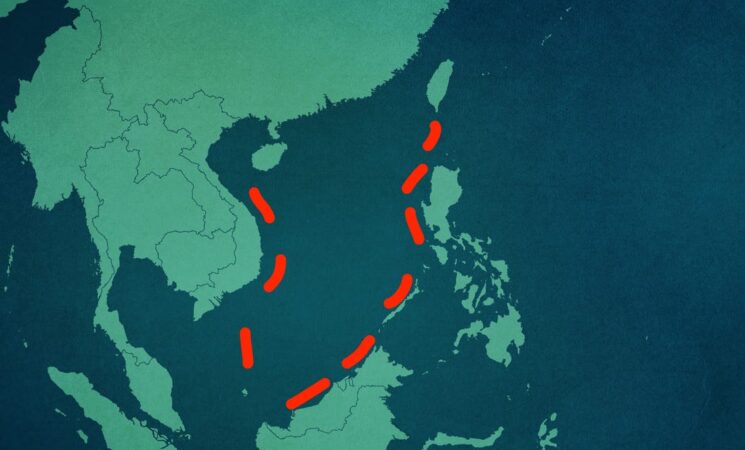

The South China sea is a 3.5 million-square-kilometre embroiled in a territorial dispute between China, Vietnam, Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei. Vietnam exerts its claim over the Paracel and Spartly Islands, while southern parts of the sea along with some part of Spartly Island are claimed by Brunei and Malaysia. The Philippines is yet another claimant of the Spartly archipelago and Scarborough shoal. Last, but undoubtedly not the least is China which claims almost 80 percent of the sea by devising the ‘Nine-dash-line’ as a geographical marker.

The sea is valued for its richness in resources with 10 percent of the world’s fisheries found here. It is also abundant in undersea energy resources of oil and natural gas. Furthermore, nearly 40 percent of the global shipping passes through it, with Strait of Malacca being a major chokepoint. All these factors make the sea an economically and geo-strategically vulnerable and contested maritime zone with various countries seen exerting their claims and trying to make their presence felt.

China’s Aggressive Stance

With the latest Chinese move of issuing new names for 80 islands, reefs and other geographical structures, apart from creating artificial islands, China is leaving no stone unturned in asserting its claims in the SCS. It has gone another step ahead in establishing two districts to administer Paracel and Spartly islands. The use of land reclamation process, militarising the islands with missiles, air-strips, long range guns and troops, pursuing aggressive patrolling to deter disputants, harassing fishermen in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of other nations and setting up of research station on the islands are few of the ways in which China is practising ‘Coercive Diplomacy’ in the region. If that weren’t enough, it has been accused of unilaterally altering flows of the Mekong river that have caused droughts in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

A glimpse of the Chinese audacity was witnessed in 2016 when it released a White paper against the verdict of an UN backed tribunal, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which struck down the historical rights of China in the sea. The negotiations on formalizing a Code of Conduct also didn’t see the light of the day and its legal status remains undefined.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which plans to connect various continents through marine means and roadways, will help China in deepening its economic stronghold in the region. Additionally, on 1 April 2020, China launched the ‘Blue Sea 2020’ plan which involves its multiple agencies coming to the forefront in cracking down on offshore oil exploration and exploration activities by other countries.

A probable increase in China’s military might in the sea can be speculated with the off late increment in its defence expenditure to USD 179 billion from USD 177.6 billion last year. Although the percentage increase is lower as compared to previous trends, it holds significance in the light of the global COVID-19 outbreak as it sheds light on China’s expenditure priorities. This will unambiguously be utilized to further contribute to its objectives of naval modernisation.

Just when one would think that with the COVID-19 crisis showing no signs of de-escalation, China would tread a little slow on its policy of aggressive expansionism, China has opened up a lot fronts together, as is evident in its regular quagmires in the SCS, the sovereignty challenges it poses to Taiwan and Hong Kong and not to mention the Ladakh and Sikkim face-off.

The US and China: Head on Collision

The US is actively making its presence felt due to multiple reasons. Firstly, the U.’s shift in stance from ‘Asia-Pacific’ to ‘Indo-Pacific’ has catalysed its involvement in the South and East Asian region. It has been actively pursuing military expeditions and has laid emphasis on enhancing bilateral economic relations with the countries present in this region. It has repeatedly insisted on free navigation of commercial vessels in the SCS, which is indispensable for uninterrupted regional and international trade, as many of the global supply chains involving American companies which produce goods in this region are dependent on it.

Secondly, China’s assertiveness has been a chronic eyesore for the US, which is not yet ready to do away with it position of global hegemony. It has security commitments in East Asia and is allied with countries such as the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam. It has stepped up its naval presence and has been conducting joint exercises along with surface vessel and submarine war games with marines in the SCS. On 15 May 2020, it deployed USS Rafael Peralta Arleigh-Burke-class destroyer some 116 nautical miles off China’s coast. It has also been conducting Naval drills and Freedom of Navigation Patrols in order to convey to China that these are international waters and are not subject to claims by any particular country. To further strengthen the ASEAN and East Asian countries militarily, the US has been providing financial support and concluding bilateral defence collaborations.

The face-offs between the US and China have not all been in the seas. The undercurrents have been felt even in the UN forums such as World Health Organization (WHO) where the war of words and blame gaming has tended to push the world towards a state of paralysis.

India’s Stand

India abides by the policy of non-intervention when it comes to the SCS. Absence of any significant stake in the zone as well as its willingness to preserve its ‘Wuhan consensus’ of 2019 with China wherein both nations committed to respect each other’s spheres of influence in their adjacent water bodies, have prevented India from directly showing involvement in the sea. Furthermore, India’s refusal to join RCEP further diminishes its vulnerability from China’s dominance in the sea.

Notwithstanding the above, India’s bilateral ties with nations in the Western Pacific will surely help circumvent the unpleasantries being exchanged in the SCS. The visit by the Indian Defence Minister, Rajnath Singh to Tokyo in September 2019, to review the security cooperation between the two countries in the Indo-Pacific region and the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement with Russia to open a maritime route between Russia’s eastern port city and Chennai, display India’s strategy of fulfilling its aims without prodding China directly. However, it would surely serve India positively if China is contained as China’s military installations in the SCS can pose security risks to India.

To check China’s unobstructed dominance in the SCS, global players such as multilateral groupings of ASEAN and East Asian Summit should exert pressure on China to contain its activities in the region. A legal framework needs to be devised wherein the rights of various claimants in the sea are documented and defined in accordance with the guidelines mentioned under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). There is a need for a robust mediation, facilitation and binding resolution mechanism which encourages joint development zones.

China’s aggressive expansionism coupled with the lack of fear of penalization is slowly making it adopt a ‘care to hoots’ attitude. With the US losing its credibility in the light of its backtracking on commitments, exit from various deals, etc, it will further become difficult to regulate China’s stubbornness. Mere military engagement will be of little or no avail. It should be combined with consensus building measures. Since China works on a quid pro quo basis, why not offer it some deal it cannot refuse.