10 June 2025, NIICE Commentary 11234

Dibya Deep Acharya

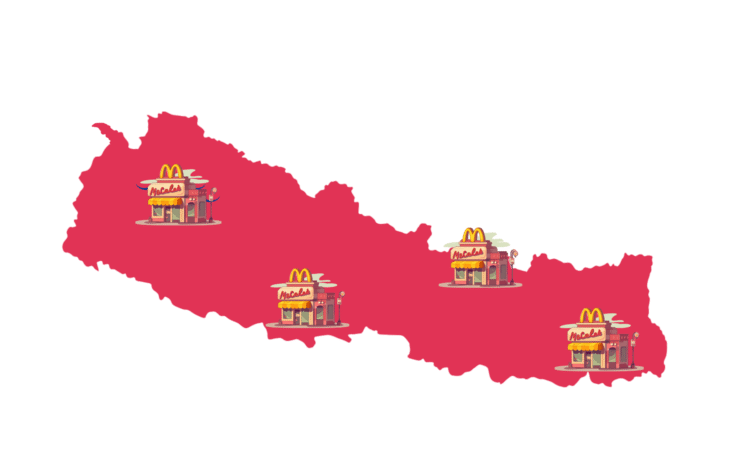

Scholars have often pointed out how economic integration can be an invisible hand of peace, as a form of international stabiliser against threats. Before diving into this paper’s subject matter of Nepal needing economic integration, it needs to be pointed out that the idea of “needing a McDonald’s” for peace is not about burgers, but about economic ties and shared interests.

Thomas Friedman’s Golden Arches Theory first wryly observed that “no two countries that both have a McDonald’s have ever fought a war against each other”. While tongue-in-cheek and rhetorical, he later expanded his ideas by stating that, as long as the supply chains span multiple countries, those nations will avoid conflict to protect their economic stakes. Meaning, the idea is simple: if your country is integrated more in terms of trade, regionally, multilaterally, or globally, then there is a higher chance of your security without the need for explicit hard power or deterrence.

McDonald’s: More than just Fast Food

Friedman’s original quip linked the global spread of McDonald’s to the rise of middle-class consumerism and the decline of war incentives. Critics of the Golden Arches Theory quickly pointed to counterexamples such as NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 or Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, among many other examples of democracies going to war, as proof that franchises alone cannot guarantee peace. But the theory in my belief argued more than just franchises. It wanted to explore an idea of global integration backed by capitalist peace theories. It talked about how economic integration today, through globalisation and thousands of treaties, deals, and economic leverage, war has become an almost ‘zero-sum game’. No two countries today will go to war if they have more to lose; that’s a capitalist peace assumption, but of course, war and its ideas are far more complex than just economics.

The idea of McDonald’s (the franchise) and Peace was brought out in Thomas l Friedman’s Book "The Lexus and the Olive Tree"

The Invisible Hand of Peace

Thus, though not an assurance of guarantee, scholars for decades have urged the need for economic integration as a soft resistor to war. Firstly grounded by the ideas of Immanuel Kant’s Perpetual Peace and what later became Democratic Peace Theory argues about this in-hand idea- republicans do not go to war. In simple terms, why would nations risk their own economic damnation, as one assumes, nations are rational? But, democracies for years have gone to war. Even regionally, conflicts between two giant democracies, India and Pakistan, are evident to the idea that even though nations are rational, the reasons for war usually aren’t. But, there does exist an invisible hand of peace through economic mutual dependence.

1971, the third Indo-Pakistani war, the signing of the documented instrument of surrender in Dacca.

Relevance for our sovereignty

Especially relevant for Nepal is the idea to seek such invisible hands of peace. UN does not guarantee peace for Nepal, nor do its ‘balanced’ ties with India or China. Treaties of Peace and Friendship are only treaties if respected by two nations, and as seen during the case of Ukraine, the international system falters when hegemons grab what they want. Nepal is often called a yam between two giant boulders, though it does not have an imminent threat; the international state of anarchy compels it to secure its self-sovereignty, perhaps not through arms or hard power but perhaps through these ideas of economic dependence.

Though the two paragraphs above present a bleak view of Nepal (almost in a realist perspective), the ethos of these statements is to only provide merit to the idea that Nepal, as any other sovereign Non-Aligned Nation, truly stands alone with no security guarantees. With ongoing border frictions such as Kalapani, Susta, and strategic overtures from China, perhaps now more than ever is the time for such peace tenets to become more prominent.

The Economic Aspect of Nepal

Nepal’s exports account for merely around 6% of its GDP (among the lowest in South Asia), which highlights its marginal position in global trade. Such economic isolation weakens Nepal’s bargaining power and heightens vulnerability to external pressures. By pushing higher focus on Nepal to increase its trade not just with India but other countries, perhaps Nepal may guarantee this so-called Invisible Hand of Peace.

But how?

Geographic Placement

Nepal lies between two giant boulders, as mentioned in the Divya Upadesh. The two neighbors, India and China, are the largest in terms of growing economies and population. As many scholars have pointed out, and with historical anecdotes where Nepal has been a hub of transit, Nepal can become a transit hub that offers ‘unparalleled and preferential access’ to both markets. Moreover, adapting to these giant economies through niche-based export marketing, preferential bilateral agreements, and subsidised product placements can help Nepal deepen not just existing pacts but also help Nepal negotiate new ones to expand to export markets with the help of its neighbors. Lastly, the South Asian region itself is an untapped market full of potential. Initiatives like the BBIN sub-regional integration can help reduce transit costs and foster cross-border commerce. Adding to this, regional channels like SAARC, BIMSTEC could be the way for Nepal’s much-needed economic integration.

The Multilateral Element

As a WTO member since 2004, Nepal can use its voting rights as well as the forum itself to advocate for fairer market access and safeguard its economic interests. Beneficiary status under the EU’s Everything-But-Arms scheme and eligibility for GSP+ can secure tariff-free entry for virtually all Nepali goods. Moreover, the multilateral element is something Nepal is yet to completely build upon. Preferential Trade Agreements and BIPPA (Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements) can be a tool for Nepal to leverage to penetrate the global trade market. Furthermore, as mentioned above, with the niche-based market orientation, Nepal’s uniqueness should serve as Nepal’s way forward for trade integration. Its herbal, spiritual, textile, carpet, rich culture, and cuisine can become a product that can integrate itself and match the world trade.

The Building of a Brand

Improving Nepal’s rank in the Global Soft Power Index (currently 105th) and promoting cultural exports can enhance global demand for “Made in Nepal” products. Taking notes from countries like Japan and South Korea can help Nepal understand how nations can build brands through the cultivation of soft power. One thing Nepal is rich in is diversity, its richness in culture and multi-ethnicity. All of these elements can become a reason for soft power cultivation that isn’t only limited to building an image, but rather a brand. Furthermore, with remittances constituting almost 30% of its GDP, building channels for diaspora investment schemes and skills-matching platforms can channel expertise and capital into export-oriented ventures. Lastly, opening sectors such as agro-processing or even tea diplomacy to foreign investment can drive technology transfer and scale up export capacities

Beyond Rhetoric and Towards Resilience

These are just some basic tenets on how Nepal can actually integrate itself into the global trade, but for that, internal policies and stability need to be achieved. But, coming back to the ethos of this paper, Nepal does not literally need a McDonald’s to keep the peace ,but it does need the deep, sustained economic linkages that such franchises metaphorically symbolise. Perhaps in doing so, Nepal can write a new chapter in its own security narrative. The invisible hand of trade may not guarantee perpetual peace, but it can make war a cost far too great to bear and Nepal can make that happen by leveraging NTIS (Nepal Trade Integration Strategy) as well as other initiatives to become not a key actor in Int’l trade but an actor of some influence, leverage and stake.

Dibya Deep Acharya is currently pursuing his Master's in International Relations and Diplomacy, Tribuvan University, Nepal.