26 July 2020, NIICE Commentary 5658

Karnika Jain

Given that the radicalisation and terrorism in the region are being studied extensively for a long time, the region still is confronting the blight of the problem. The South Asian region has faced a multitude of challenges ever since the countries got independent. But one of the challenges that South Asia faces today is the rapid growth of radical tendencies. Thus, when combined with terrorist violence, it poses a major threat to peace and security of the region. As per the report of Global Terrorism Index 2019, South Asia is recorded as the world’s most affected region by terrorism.

Worldwide, youths have been at the target point of the radical and terrorist organisations for training and recruitment and South Asia is no exception when dealing with this threat. The trend is further strengthened by the statement of the United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Guterres that because of the potential and enthusiasm for change, young people are on a target point of violent extremist groups. What makes the region more vulnerable is that around half of its population is below the age of 25 years. This makes a potential fertile ground for mushrooming of “youth bulge” theory and its implications on peace and security of the region. The theory states that a group of youth who are unemployed are generally gullible and could fall easy prey to the trap of radicalisation.

While standing at this juncture, it becomes important to go deeper to understand the reasons for the increase of youth radical dispositions leading to terrorist activities. It would be studied in the context of the prevailing political system, social structure and economic profile of the countries.

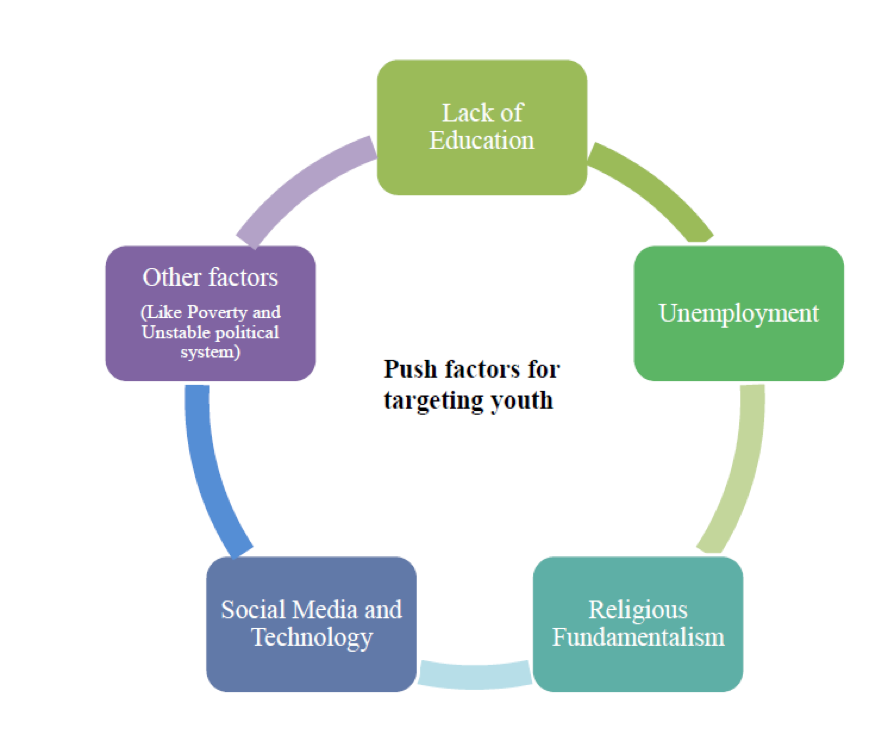

Push Factors for Targeting Youth

Peculiar privations have always been a major problem in the region for youth to get attracted to radical organisations. One of the factors is the poor education system that creates disenchantment in the youth. Despite the fact that education is essential for development and well-being of society, the overall regional spending on education is just 2.1 per cent of its GDP in 2018, which is gradually declining every year, as per the World Bank. Moreover, in congruence with the Report of UNICEF, around 95 million children of school going age have been left out from the formal education system. These limitations of accessible quality education create a conducive environment for the terrorist groups to exploit the youth.

Similarly, the low conversion rate of youth from education to the alley of employment is another hurdle faced by youth in the region. The 2019 edition of the UNICEF shows around 54 percent of the youth in the region conclude their schooling but have absolutely no skills which would fetch them a decent source of earning in future. The sluggish economy, low wages, vulnerable job sector, income disparities or prolonged unemployment create an easy route for terrorist organisations to tap on these unfulfilled minds. Income inequality creates social tensions and tends to contribute to social and political instability. A report from the World Bank confirms that unemployed youth dropouts are vulnerable to violent or criminal activity to vent out their frustration.

Similarly, the low conversion rate of youth from education to the alley of employment is another hurdle faced by youth in the region. The 2019 edition of the UNICEF shows around 54 percent of the youth in the region conclude their schooling but have absolutely no skills which would fetch them a decent source of earning in future. The sluggish economy, low wages, vulnerable job sector, income disparities or prolonged unemployment create an easy route for terrorist organisations to tap on these unfulfilled minds. Income inequality creates social tensions and tends to contribute to social and political instability. A report from the World Bank confirms that unemployed youth dropouts are vulnerable to violent or criminal activity to vent out their frustration.

The radicalisation landscape is diverse in nature and pathways of joining these groups are extremely multifaceted. The attack in Bangladeshi Holey Artisan Bakery in 2016 or the Sri Lankan Easter attacks in 2019 reflects that irrespective of education and socio-economic background, youth of any type could be radicalised and could be influenced to be involved in violent extremism. These shifting economic profiles of new targets make countries additionally vulnerable to the radicalisation process and pose a daunting challenge in the region. Unfortunately, there are many reasons for youth to be driven into extremist activities. Notably, one of the major reasons could be influx of fundamentalist religious ideologies seeding mutual animosity amongst people. The region comprises of multi-lingual, multi-religious, multi-ethnic identities in which communal and religious ideology play a powerful role to fracture the societal cohesion. The propaganda machinery at religious afflicted places and brain hijacking of young minds that have malleable view of the society and religion makes the scenario favourable for terror groups.

The other problems that sow the seeds of frustration, disengagement, and unrest amongst youth are the long-sustained poverty, destabilised economy, social insecurity, communal deprivation, deteriorated service delivery and corrupted and unstable political system. Similarly, 2016 Edition of the Global Youth Development Index report states that worldwide, the region recorded the second lowest levels of youth development after Sub-Saharan Africa. Taking the advantage of these situations, radical ideas are exposed to youth in order to address their grievances. In addition, the densely populated region has additionally created pressure upon existing resources that has profound implications for generating societal conflicts.

Another reason for terrorists to display their interest in the youth is their active presence on social media. Penetration of the internet is playing a great role in radicalisation and recruitment of young people. Hi-tech media opens a wide window for terrorists to reap benefits of despair youth in spreading their radical ideologies. Hence, while the South Asian governments are involved in curtailing terrorism through operational measures, countering radicalisation remains one big challenge. Radicalisation is an ideological threat, and to combat this, the countries need to come up with strong counter-ideology and counter-narrative measures.

Way Ahead

Reflecting on the fact that even the youth belonging to a well-to-do family with a decent educational background are getting radicalised, it is highly critical for the states of South Asia to revisit their response mechanism vis-a-vis the threat of radicalisation.

First, there is a need for governments to focus on tapping the enormous energy and potential of the youth. If channelized constructively, the dynamism that youth brings to the table, could become a contributing factor for socio-political progress in South Asia. Educational reforms need to be brought in where the kind of education imparted to youth could incorporate mandatory brainstorming and counselling sessions. Also, enough employment opportunities and innovation hub centres should be welcomed where the youth could pitch in their ideas and could get the right guidance.

Secondly, countering radicalisation is a process which would take years of appealing conversation. The regional faith based society need to be promoted by more tolerance and rationality. An ideological indoctrination amongst youth needs to be opposed by equal resource distribution along with stable social and political securities.

Thirdly, the region lacks the common platform where one could discuss the problem of radicalisation and devise strategies to thwart the attack. The region faces the cross-border terrorism but regardless of this, lack of collaborated mechanism and information sharing prevails.

Lastly, in dealing with the scourge of youth radicalization and terrorism, the states need to facilitate more public awareness programs where the new trends of radicalization could be identified at an early stage. There is a need to resolve social unrest with more inclusion and peace-building platforms. Security analysts also need to work hard on curbing threats emerging from cyberspace. The states need institutions which could effectively reach out to the community to ensure that youth are on the right track of development.

Therefore, the threat of radicalisation and terrorism is real and to evade this threat, it is prerequisite to ensure continuous collective measures.