13 November 2025, NIICE Commentary 11927

Dr. Md. Abdul Latif

As interdependence deepens, the one-center model of trade governance is giving way to a web of regional accords, bilateral deals, and multi-stakeholder initiatives. Rising multipolarity has weakened the legitimacy of global bodies and fostered a polycentric system in which producers meeting sustainability standards serve fast-growing markets in both the Global South and the North. Defined by multiple decision-making hubs rather than a single authority, this approach better reflects 21st-century power and interests. Is it the future of global commerce? Amid inequality, geopolitical friction, and shifting alliances, policymakers and businesses must understand its implications. This op-ed assesses the promises and risks of polycentric trade and its potential to advance equitable, sustainable exchange.

The architecture of global commerce is shifting. The postwar liberal order—anchored by the WTO and major Western economies increasingly challenged by regional, plurilateral, and issue-specific agreements. The diffusion of trade power, accelerated since the pandemic, has entrenched polycentric governance: multiple actors, institutions, and regions now write the rules simultaneously rather than under a single normative center. As the world economy grows more fragmented yet interdependent, polycentric trade governance is becoming the norm.

Evolving the Concept of Polycentric Trade Governance

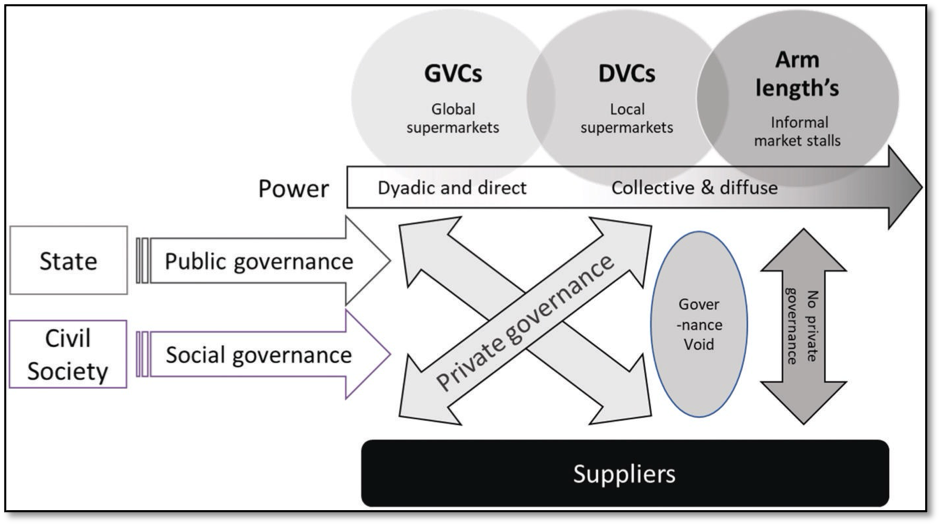

Figure: Governance-power in a context of polycentric trade (M. Alford et al, 2024)

Horner and Nadvi define polycentric trade as the interweaving of global and domestic value chains (GVCs and DVCs) across multiple Northern and Southern end markets. Polycentric systems operate with multiple semi-autonomous authorities interacting within shared domains. In trade, this translates to suppliers and states engaging across the Global North and South value chains. Unlike the earlier Northern-led model, developing economies now participate in diversified supply networks, serving multiple markets simultaneously.

The evolution of polycentric trade reconfigures power and responsibility. Governance once concentrated in northern corporate or state hands is now shared among private firms, national regulators, and social actors. Lead firms still coordinate global supply chains, but governance varies: high-complexity products tend to involve hierarchical control, while standardized goods rely on looser networks and voluntary standards.

Trade regulation has likewise become polycentric. Alongside the World Trade Organization (WTO), states pursue regional and plurilateral agreements tailored to their needs—such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia and the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) in North America—creating a more adaptable policy environment.

The rise of Southern economies has prompted reassessment of whether global governance matches current realities and has challenged North-centric decision-making (Efstathopoulos, 2021). RCEP now covers all 15 members and, according to the Asian Development Bank (2024), could add nearly US$200 billion annually to members’ real income by 2030. Its simplified rules of origin and digital trade provisions show how “southward” governance can deliver gains without a dominant Western hub. Southern actors increasingly contest institutions such as the WTO and IMF (Zarakol, 2017 and Hopewell, 2022) and advance alternatives that reflect Southern interests (Chin, 2014).

Polycentric trade governance is not disorder but an adaptation to complexity: diverse economies and regulatory systems cannot be managed under a single umbrella. From 2022 to 2025, the world has become more multipolar. BRICS expanded to include Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia, forming a Southern-led bloc representing nearly half the global population and about one-third of global GDP. African integration via the AfCFTA is advancing as more than 40 countries implement tariff cuts and digital trade protocols.

These shifts challenge the view that trade governance should run exclusively through the WTO or trans-Atlantic frameworks. States are “scaling across” institutions via overlapping memberships—pragmatic pluralism. According to the WTO’s 2024 outlook, global trade volume grew 1.2% in 2023 and is projected to reach 3.3% in 2025, suggesting resilience now rests more on regional and sectoral diversification than centralized management.

Potential Welfare Impact of Polycentric Governance

Polycentric trade governance could reshape global welfare by making trade more efficient, competitive, and inclusive. With multiple centers of negotiation and decision-making, it allows countries to move faster and tailor deals that reflect their own economic realities.

Greater Efficiency

Unlike slow-moving global talks, polycentric governance lets countries strike regional and bilateral deals that address local priorities and changing conditions. By cutting tariffs and non-tariff barriers more quickly, these agreements can boost trade flows and make resource use more efficient — delivering tangible gains for producers and consumers alike.

More Choice, Lower Prices

Competition between overlapping trade regimes expands consumer options and encourages innovation. As markets open and regulatory approaches diversify, consumers enjoy a wider variety of products and lower prices. The pressure to compete keeps firms sharp — driving better quality and new ideas across industries.

Empowering Smaller Economies

Smaller and developing countries stand to benefit the most from a polycentric system. Multiple negotiation platforms give them more voice and flexibility to pursue their interests. Regional pacts often come with capacity-building measures and technical support, helping these economies strengthen their trade institutions and compete on fairer terms in global markets.

The Challenges of Fragmented Norms

Regulatory Complexity

Multiple regimes create conflicting standards and increase compliance costs. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), phased in since 2023, exemplifies climate measures that many emerging economies perceive as disguised protectionism. Simultaneously, U.S.–China decoupling and “China + 1” strategies reinforce bifurcated supply chains defined by ideological and technological competition.

Inequitable Power Dynamics

Polycentricism risks deepening asymmetries. Larger economies often dominate smaller partners in regional or bilateral arrangements, setting rules that favor their own interests. In RCEP, smaller Southeast Asian countries fear China’s economic leverage, while African states negotiating with the EU face pressure to adopt stringent regulatory standards that exceed their institutional capacity. Without safeguards for equity and transparency, polycentricism may simply reproduce the inequalities it seeks to dismantle.

Risk of Downgrading Standards and the Dynamism of Welfare

Without global benchmarks, states may relax environmental or labor regulations to attract investment. This “race to the bottom” erodes welfare, undermines sustainability, and especially harms vulnerable, commodity-dependent economies.

Coordination Difficulties

Overlapping institutions impede progress on global issues that require collective action—among them climate change, AI governance, and labor standards. Divergent digital governance regimes, such as the EU’s 2024 AI Act and emerging ASEAN frameworks, illustrate the risks of siloed innovation and higher transaction costs for global firms. Maintaining interoperability among major trade hubs is therefore essential to preserving the efficiency gains of decentralization.

The Future of Global Commerce and Lessons for South Asia

South Asia’s trade remains fragmented despite shared geography and complementary economies. A polycentric world offers both opportunity and risk: more scope to diversify partnerships, but also a greater need for regional coordination.

To benefit from this evolving order, South Asian countries should:

- Deepen Regional Cooperation: Reinforce mechanisms such as BIMSTEC and a revitalized SAARC to harmonize standards, streamline customs, and develop cross-border logistics.

- Diversify Partnerships: Reduce dependence on Western markets by expanding trade with ASEAN, Africa, and the Middle East—key players in the new polycentric landscape.

- Build Institutional Capacity: Invest in expertise on digital trade, dispute settlement, and regulatory design to engage effectively in plurilateral negotiations.

- Strengthen Infrastructure: Upgrade transport, ports, and digital networks to cut trade costs and attract investment. Integrating SMEs into regional and global value chains will broaden the gains from trade.

- Balance Autonomy and Cooperation: Engage flexibly with multiple partners while aligning with global norms on sustainability and data. Transparent negotiations and inclusive policymaking are critical for legitimacy

Conclusion

Polycentric trade governance marks a clear shift from centralized control to a network of overlapping systems. The task is not to resist this change but to guide it toward inclusiveness, resilience, and shared prosperity. The WTO should evolve into a coordinating platform that harmonizes global rules on digital trade, climate policy, and supply-chain security, while regional blocs such as ASEAN, BIMSTEC, and AfCFTA prioritize interoperability over influence.

For smaller economies, agility is crucial—adapting to varied regulatory regimes, building strategic coalitions, and amplifying their collective voice. In doing so, South Asia can become a key bridge among emerging trade hubs. If managed with foresight, this multipolar order can democratize rule-making and make globalization more balanced, participatory, and truly representative of an interconnected world economy.

Dr. Md. Abdul Latif is the Additional Director at the Bangladesh Institute of Governance and Management (BIGM), Bangladesh.