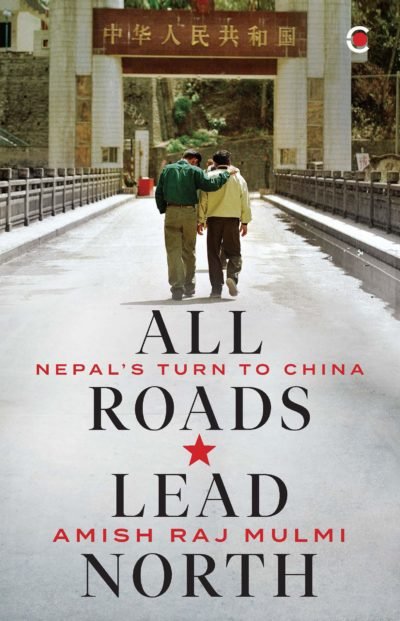

Amish Raj Mulmi (2021), “All Roads Lead North: Nepal's Turn to China”, Chennai: Westland Publication Private Limited.

Shila Parajuli

All Roads Lead North: Nepal's Turn to China brings Nepal's relation with China from the historical perspective and highlights peoples-peoples ties of Nepal-China relations. The author of the book Amish Raj Mulmi is a professional journalist with a long history of working with Indian publications. He has extensive experience working as a columnist for the Kathmandu Post. Mulmi's writings have appeared in numerous other publications, including Aljazeera, Himal Southasian, Roads & Kingdoms. The book justifies the title with a clear description of Nepal's relations with China from different dimensions which includes different facets, including history, geography, and politics. It also presents the geopolitical realities of Nepal being part of the significant geopolitical contest between India and China and the US, India and China.

All Roads Lead North: Nepal's Turn to China brings Nepal's relation with China from the historical perspective and highlights peoples-peoples ties of Nepal-China relations. The author of the book Amish Raj Mulmi is a professional journalist with a long history of working with Indian publications. He has extensive experience working as a columnist for the Kathmandu Post. Mulmi's writings have appeared in numerous other publications, including Aljazeera, Himal Southasian, Roads & Kingdoms. The book justifies the title with a clear description of Nepal's relations with China from different dimensions which includes different facets, including history, geography, and politics. It also presents the geopolitical realities of Nepal being part of the significant geopolitical contest between India and China and the US, India and China.

The book starts with the historical context that shape contemporary Nepal-China relations. It follows three central themes: Northern Borderlands, Post-1950 history of Nepal-China relations, and post-2008 relationship between Nepal-China. Comprising of ten chapters, the author routes through the history of Nepal-China relations from the tale of trade between ancient Tibet and Newar merchants of Nepal. Unlike the prevalent narrative that the Himalayas are the static frontiers, the book brings an entirely dynamic perspective of Himalayan borders. The author brings in people’s viewpoint of the border; how the Northern border is an economic resource for local communities living in Nepal and a solid psychological and cultural influence of Tibet that exists. The second theme takes us to post 1950s relations between Nepal and China. It is basically about how a social link got transformed into political and legal associations - diplomatic relations between Nepal and China, the influence of Maoism on Communism in Nepal, and the issue of Tibetan refugees. The last three chapter attempts to analyze Nepal-China relations against the larger backdrop of Nepal-India relations. Mulmi has compared the Chinese response to the unofficial Indian blockade to Nepal of 1989 and 2015. This part of the book also talks about the Chinese flavor of capitalism that is taking place in Nepal. The Chinese investment is visible not only in the borders but also in the streets of Kathmandu. It also brings in the asymmetric nature of Nepal-China relations; like every great power-small power relation, and the unilateral control of China in the northern borders.

The book attempts to address the research gap in South Asian scholarship that views South Asian countries only from the security perspective and extensively ignores people-to-people relations. It drops the India-first narrative and focuses on Nepal’s historical ties with Tibet and China. It is not an academic book and the beginning part of the book mostly follows an ethnography approach, directly quoting people’s experiences and the interview with Himalayan communities across Humla, Rasuwa, Mustang, and others. The later part of the book uses the research method as archival research, borrowing historical records from Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA’s) declassified archives, the China News Analysis archives, the Wilson Centre’s digital archives, the Wikileaks files, and online journal sites. The author has extensively used resources of Nehru Memorial Museum and Library of New Delhi and the Martin Chautari’s Library of Kathmandu. Based on qualitative methodology, the author mostly uses primary sources and few journals as secondary sources.

The book develops a narrative format and uses easy-to-understand and straightforward themes. One doesn't necessarily need to be an international relations expert or understand politics to understand the text. The strength of the book lies in the distinct subdivisions and composition it follows. The division of the book into three specific themes makes it easier to hover over the text, meaning one can directly hop over any one of the themes without reading the former one. Anyone with basic English would comprehend it well. The author makes harsh arguments about the existing Indian scholarship based on the hubristic imperial lens that views the South Asian region from an India-first perspective. Thus, the author’s stance derives from a social and economic perspective, with some political facet. The book comes with its own set of strengths. Investing heavily on the anthropological side, Mulmi has brought the Nepal-China relations in completely raw form and the narrative style of writing makes the audience close to the Northern borders. The book doesn't use any grand theory to explain Nepal-China relations but brings insight into how Nepal and ordinary Nepalis view the North. The last part of the book heavily takes the political route that could have been omitted. Also, the mention of MCC seems quite out of context. Instead, the economic and strategic opportunities and challenges of BRI would have been relevant. Similarly, it would have been worthwhile if the author had brought the story of Mountain Sherpas of Nepal, and their perception of China. However, the author seems to have achieved the stated purpose, which is to portray the social and economic aspects along the Nepal-China border. The book is beneficial for scholars, policy makers, journalists and common people and I would strongly recommend everyone to read this book.

Shila Parajuli is Research Intern with NIICE.